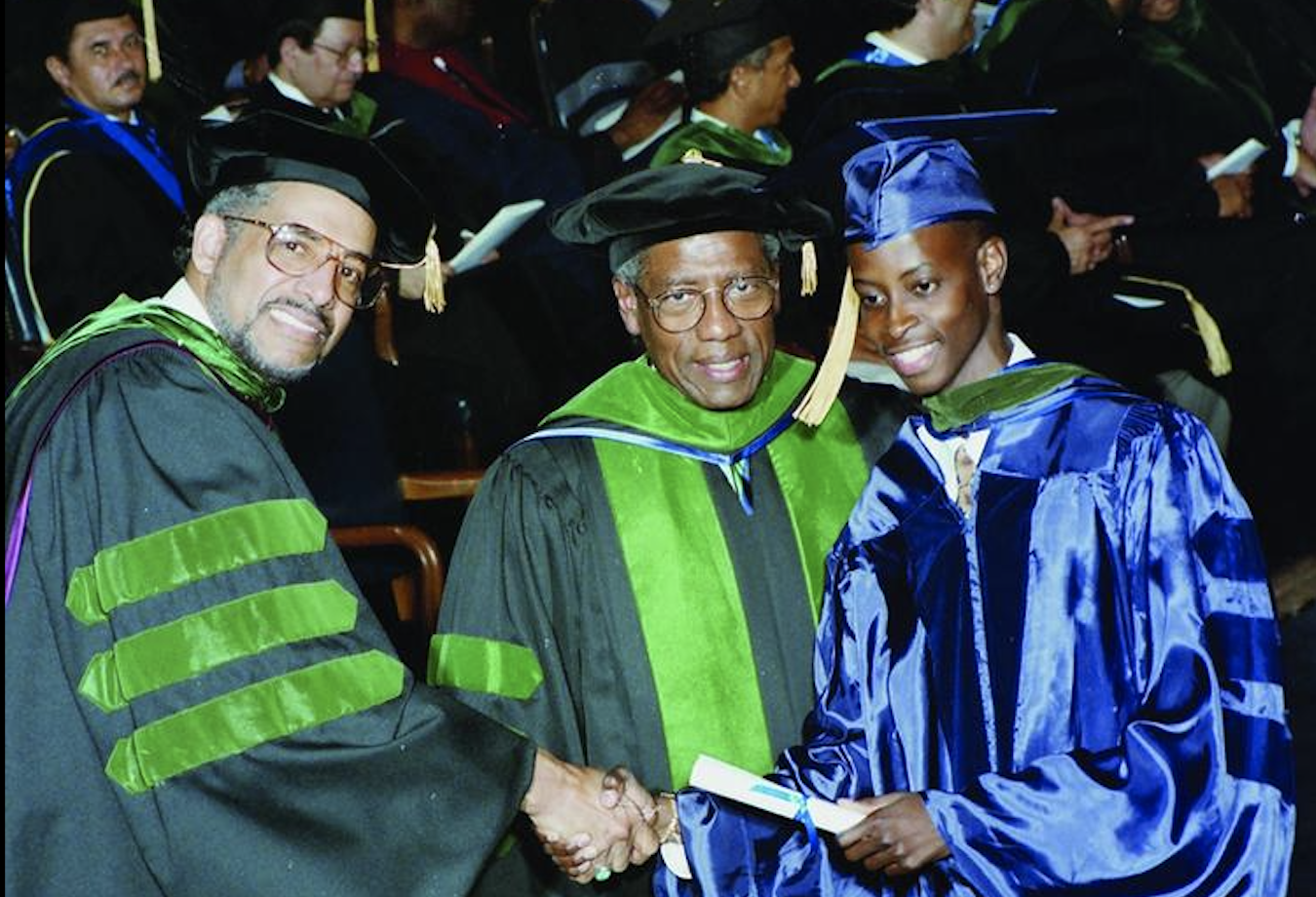

The story of Dr. Wayne A. I. Frederick’s illustrious college career at Howard University, one that would culminate in the earning of three degrees – a bachelor’s degree in 1990, a medical degree in 1994, and a master’s in business administration in 2011 – began with a missed deadline and a recurring case of mistaken identity.

Back home in Trinidad and Tobago, Dr. Frederick recalls, Howard was regarded as the big name school – the university everyone aspired to attend. His best friend from childhood, Shaka Hislop, was already there and urging to submit his application. So he did. It was the only university he would apply to.

First Steps on Campus

He was 16 years old when he received his Howard acceptance letter at his home in the city of Port of Spain. Yet despite all his focus and dedication on getting into Howard, he was largely unaware of the steps he needed to take to actually matriculate.

“When I applied to come to Howard, I knew nothing about housing and those types of things. I had no concept of residence halls,” Dr. Frederick says. “I missed the on-campus housing deadline, so I had to live in Brookland in Northeast D.C.”

Dr. Frederick’s morning commute on the bus was a feature of his freshman year. Many of the passengers were students at Benjamin Banneker Academic High School, just on the other side of Georgia Avenue, opposite Howard’s campus. Due to Dr. Frederick’s relatively young appearance, he was often assumed to be a high school student rather than an undergraduate.

“I weighed less than a hundred pounds soaking wet,” he says. “The Banneker students assumed I was one of them.” But as they got off the bus, the high school students went one way, and Dr. Frederick went another – towards Howard’s campus.

Once on campus, Dr. Frederick claims he did little to distinguish himself from his peers and that his slight stature was about all that set him apart.

“If you lined up all the students in my class and put those most likely to one day become president of Howard at the front, I would have been at the end of the line,” Dr. Frederick quips.

Not only was he curious; he was unwilling to accept no for an answer.”

Carving a Career Path

While his path to the presidency might have been unconventional, those who knew him at that time say they can see the president he would become in the student that he was.

In an academic setting, Dr. Frederick was regarded as a top student in both his undergraduate and medical school classes.

“I’ve known Dr. Frederick since he was a medical student. One of the first things that comes to mind is that he’s probably the most inquisitive and curious student I’ve ever had,” says Clive Callender, professor of surgery at the Howard University College of Medicine and founder of the National Minority Organ Tissue Transplant Education Program. “[He wanted] to know every step I took … and understand why I was doing things.”

Dr. Callender notes that Dr. Frederick’s curiosity did not stop at medicine or surgery. Particularly for those he considered to be his mentors, he wanted to glean any and all wisdom they had to offer – about medicine, of course; but later, about also being a good husband, a good father, and a good person.

“All those things seemed to captivate him,” Dr. Callender says. “Not only was he curious; he was unwilling to accept no for an answer.”

As a person with sickle cell disease, Dr. Frederick was often told throughout his academic career that he should abandon his aspirations of becoming a cancer surgeon. But at Howard, he not only received essential care for his condition at the Center for Sickle Cell Disease, but he found people who encouraged him to pursue his highest ambitions.

“People in positions of authority at the time told him he could not become a surgeon because he was a sickle cell patient and had a splenectomy. … We were able to dispel him of the notion,” Dr. Callender says. “In spite of his sickle cell disease, he decided he was going to be a surgeon and there was nothing going to stop him, and we certainly were going to enhance his abilities to become a surgeon and not let his disability stand in the way.”

Work, Study, and Fun

Outside of the classroom, Dr. Frederick had two primary involvements. The first was as a manager of the Howard University men’s soccer team.

“I traveled with the team. And it was eye opening because I got to visit so many universities around the country,” Dr. Frederick remembers. “I had the opportunity in ’88 when I joined to see Howard go all the way to the NCAA Final Four, and actually lose in the final game. That was a really incredible start to my college career.”

LaRue Barkwell, a long-time Howard University employee, gave Dr. Frederick his first job during his freshman year as a student employee in the Office of Financial Aid.

“He was very shy. Laid back. Very tiny. Very tall. And a very gentleman-like student,” she says. “He did his job. Not a lot of chatter. Not a lot of foolishness.”

For Dr. Frederick, working in financial aid was an illuminating opportunity to learn more about higher education in the United States and to understand how people financed their educations.

“It was informative, to say the least,” Dr. Frederick says. “I understood how finances can be a big barrier for students. I learned to really appreciate other people’s circumstances.”

Dr. Frederick would repay Barkwell, in a manner of speaking, for giving him his first job. When he became president, he hired her to be the executive assistance in the Office of the President, before promoting her to chief of staff.

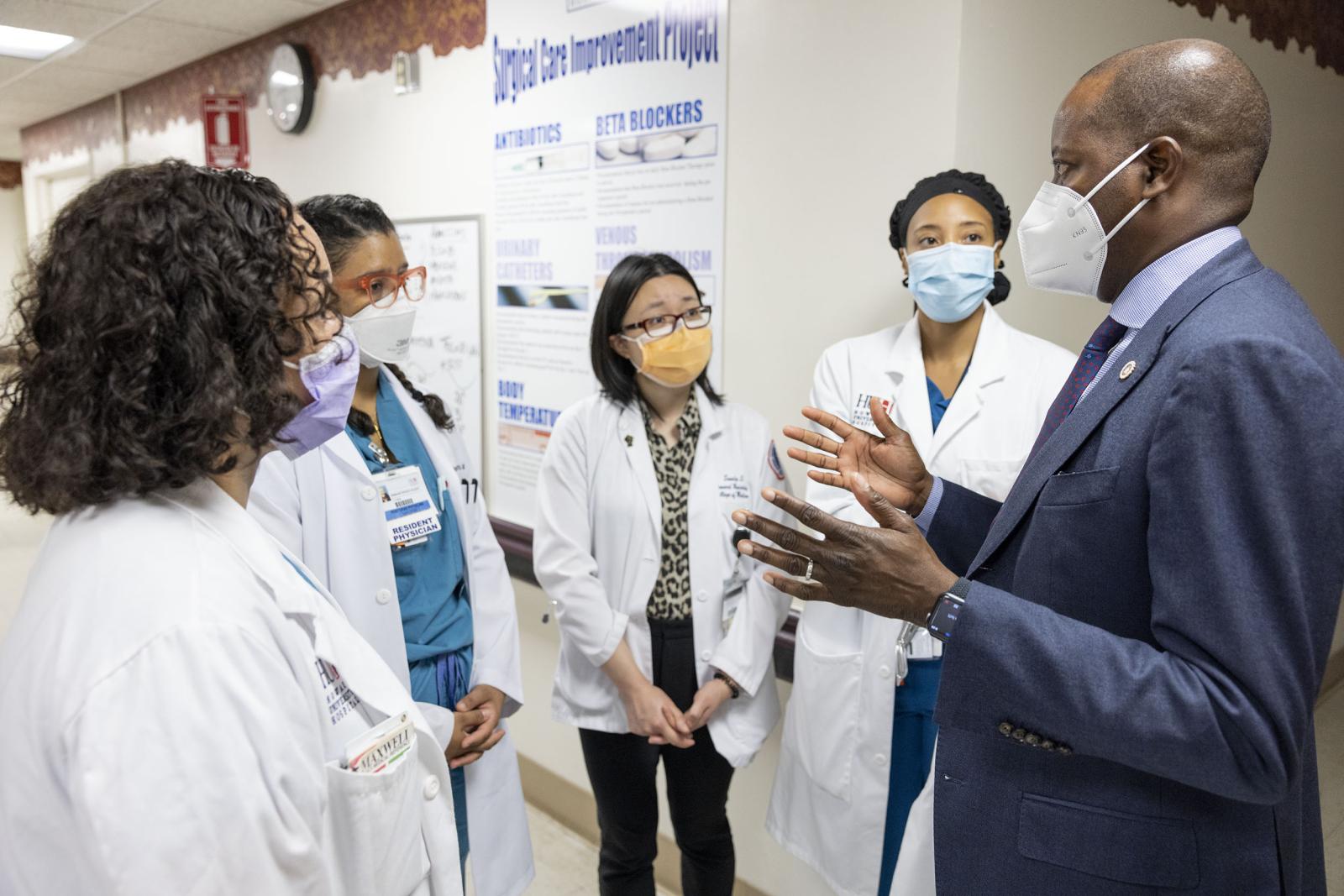

Dr. Frederick often says that his primary motivator in serving as president is to pay down the tremendous debt he has incurred to Howard University for the education he received and the work that it has enabled him to do as a cancer surgeon, faculty member, medical researcher, and more. One way he tries to diminish his debt is to foster the same love he has for Howard in the next generation of students.

“I absolutely love this place,” he said during Opening Convocation 2022, directing his comment to the new freshman class. “And I hope that you will love it, too.”

Article ID: 1201

Keep Reading

-

The 17th Presidency: A Transformational Decade

The Story of Howard University’s 17th Presidential Administration, led by Dr. Wayne A. I. Frederick

-

The Family Tree

Dr. Frederick attributes his success to the close relationships of family and friends he’s held through his life.

-

Professor Frederick

How education became the forefront of Dr. Frederick’s legacy.