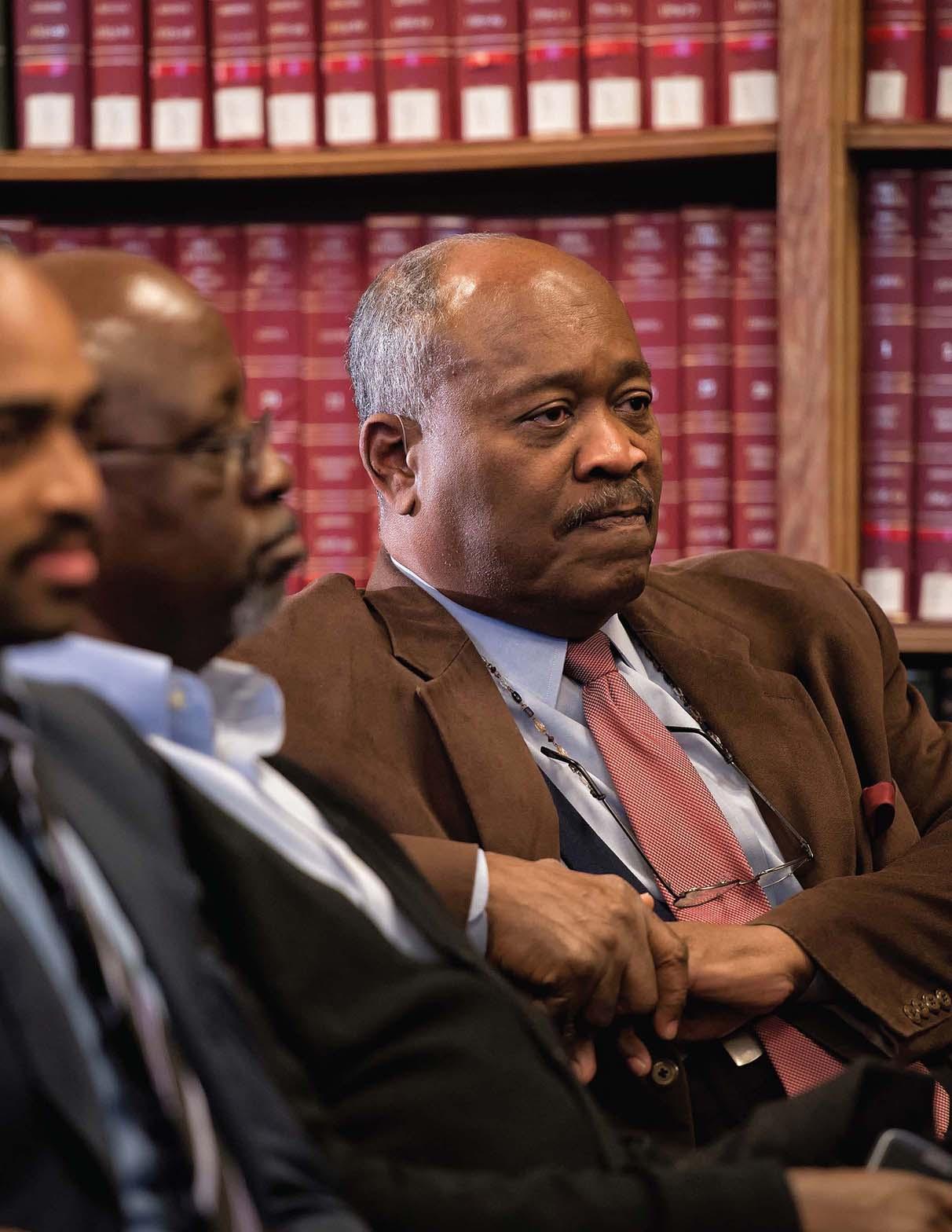

On a bright Monday morning, Colbert I. King (B.A. ’61, DHL ’18) sat across from me in grand spirits: feisty, combative, a touch wistful, and unmistakably sharp for a man fresh off his 86th birthday. It was a family affair: His wife Gwendolyn Stewart King (B.A. ’62, DHL ’18) and their daughter Allison joined the conversation, chiming in with family lore and exciting plans.

This past June, King announced his retirement from The Washington Post, but over nearly two hours of conversation, it remains clear why the man many affectionately call “Colby” became one of the foremost editorialists in American journalism.

A King at The Mecca

King’s story begins a few miles from where we sat: a native Washingtonian born “over the Georgetown, Foggy Bottom area,” a product of the preeminent Paul Laurence Dunbar High School (America’s first public high school for Black students), and if fate had followed a coach’s recruiting efforts, a potential collegiate football player outside the District. He had offers to other colleges, he recalled, but the family couldn’t afford the freight.

“I had ties to Howard and was accepted, and it was the best thing that ever happened,” he said.

King majored in government, and the department’s leadership met him with an earnestness about that selection. Within days of arriving, he said, Professor Robert Martin gathered the entering government majors to ask why they were there and what they intended to do with the discipline.

“We were nurtured,” King remembered. “When we hit our junior year and got into all of our [major] courses, we knew what we were walking into, who our professors were. We knew who was strong on the international side, who was strong [domestically], and the experts in state and local politics government. And they taught to a T.”

King also took a placement exam upon his enrollment and was placed in English 101 — “remedial English,” he jokingly calls it — where he said he first fell in love with writing, in large part to his professor, Marie Buncombe. Those first months at Howard, he was already familiarizing himself with the stacks at the Library of Congress, completing a research paper on the impact of religion in Black communities.

I had ties to Howard and was accepted, and it was the best thing that ever happened.”

“She grabbed a hold of me and found my interest in writing and composition,” King said. “It was the best grounding I ever had, academically and professionally.”

Howard’s unique vantage point widened his aperture. He describes a ROTC summer camp as a first sustained encounter with white peers from other colleges. While they had read the same textbooks, his white colleagues seemed to lack an understanding of the contemporary political movements actively shaping society’s future.

“They didn’t know anything about a Thurgood Marshall,” he lamented. “We were learning about Pan-Africanism then. My white contemporaries knew nothing about it. We had professors teaching it, people who actually experienced it.”

Names and anecdotes cascade like it was yesterday: Bernard Fall lecturing on Indochina and international relations without notes; Thurgood Marshall and his team practicing Supreme Court arguments at Howard Law; Patrice Lumumba’s delegation stopping at Howard, French-speaking students drafted as translators.

“Howard was a place where they could come, a safe haven,” King said. “We were a Mecca.”

Colbert, the Public Servant

He and Gwendolyn met at Howard and wed the summer of 1961, a month after he was commissioned a second lieutenant and received his bachelor’s degree — while she still had to complete her final undergraduate year. Gwendolyn’s memory of those years is pragmatic and warm: The community around them may not have been wealthy, she said, but what they lacked in finances, they made up for in relentlessness.

“I had to finish because I had a scholarship,” she said, assuredly. “Everybody we knew was poor. Everybody’s mother or grandmother did day work. We had to study, and if we had scholarships, we had to keep those scholarships.”

As Gwendolyn forged her own formidable career in teaching and public service, Colby’s journey would forever be changed by a happenstance meeting with fellow Howard alumnus Ronald D. Palmer (B.A. ’54), at the time an employee of the U.S. Department of State. As an undergraduate, King heard Palmer give a lunchtime presentation inside Douglass Hall, an experience that left a permanent impression.

“I’m [working] at the Civil Service Commission and walking along to get a sandwich, and I see [Palmer] walking down the street,” King said. “We talked about our Howard connection, and I told him what I was doing. He said, ‘I want you to go in the State Department building. … They’re looking to bring people in from certain backgrounds.’ That led to my joining the State Department.”

From there, King’s résumé only grows in stature: a year working along civil rights legend James Farmer at the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare on sickle cell anemia awareness; a tenure with the U.S. Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, where he helped draft the District of Columbia Home Rule Act; becoming deputy assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of Treasury, then U.S. executive director to the World Bank.

The Jump to Journalism

By 1990, King was established as a top executive in both the public and private sectors. Yet the writing impulse he’d discovered in English 101 never dimmed. Throughout his career, he was constantly writing: reports for various Senate committees, speeches delivered on Capitol Hill, articles pertaining to D.C.’s attempt at independence. He penned a guest essay for The Washington Post as the District’s new government found its footing in the ‘70s, and after years in international banking, asked the Post’s editorial leadership a simple question.

“I called [former Post editor] Meg Greenfield and said, ‘Do you think I can write?’” King said. “She said yes. I said, ‘Do you think I write well enough to join the Post?”

Those preliminary discussions would bring King to the most widely circulated newspaper in the D.C. metropolitan area, where his early workload consisted of strictly editorials for his first few years. Eventually, Greenfield suggested King start a regular column, an idea he was initially reluctant to accept.

“Let me start on a Saturday,” he demurred to Greenfield. “[Saturday] is low circulation. If it bombs, take it out of the paper. Nobody will even notice.”

More than 30 years, 1,700 columns, and a Pulitzer Prize later, King’s new vocation very clearly did not bomb, his second career arguably transcending his first. As a victory lap, he and his daughter are compiling an anthology of his best Post columns — an admittedly tough task, said Allison, given the breadth and depth of her father’s work.

“I don’t know if they’re all [his] favorite, because at one point, we put together a first pass, and it was like 150 columns,” she laughed. “We’re down to about 50 or 60, because the subject matters are so, so diverse. You name a subject, and I can pull a bunch of columns on them. That’s the variety that he’s provided.”

The Kings’ Chair

For all the accolades on the Kings’ résumés, their compass keeps directing them back to Howard. The same way a young Colby King was able to envision a life he’d never imagined while listening to guest lecturers like Ronald Palmer, he and Gwendolyn hoped to provide a similar experience to today’s Bison — the idea being that leading voices with real experience, placed in front of students at the right time, can ultimately prove life-changing.

“There’s going to be a student or somebody there, [the lecture] sets off something within them,” he said of the Gwendolyn S. and Colbert I. King Endowed Chair in Public Policy, which they established in 2008 with a $1 million gift to the university. “You don’t need 500 students to be converted. One may say, ‘Ah, I hadn’t thought about this,’ and pursue it.”

The effects have been tangible. King recalls a student who came to a session with civil rights legend Vernon Jordan, left thinking about law for the first time, and later wrote to say he’d made it his career. Another student asked a detailed policy question at a program with a former White House staffer; within days, he was at the White House talking through his query with a senior adviser.

“It’s the kind of interaction that you want to have, that you want to make possible through a King Chair,” he said. “Bringing these different resources together.”

Just as important, they understood this endowment as a means of attracting top talent to the university, if only for a year. Their vision was structural as much as inspirational.

“It was always at Harvard where somebody could go and have a year in between to get themselves ready for the next step,” he said. “We wanted to create that kind of fellowship, a chair where somebody could come hold it for a year and put together this kind of program, bringing in themselves and people from outside to talk about public policy in a real-world sense.”

While some chair choices were met with praise, others were far more provocative; it has been awarded to celebrated Howard alumni such as former President of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund Elaine R. Jones (B.A. ’65) and Rep. Elijah Cummings (B.A. ’73), and to controversial figures like former FBI director James Comey and ex-Republican National Committee Chair Michael Steele. The point, from the Kings’ perspective, is that hearing these varied viewpoints is how best to make informed decisions.

Howard University is a source of so much wisdom, training, and preparation. A Harvard could do it, but a Howard can do what a Harvard can’t.”

“All of it tells you something,” King said, “but you won’t get any of it unless you’re there to see it and experience it. There’s value.”

With a first-year granddaughter acclimating to campus and a new King Endowed Chair in Trustee Emeritus Marie Johns beginning her official slate, it is apparent that Colby and Gwendolyn King are as invested in Howard’s future as ever. While Colbert advises the university braces for the “rough days ahead,” he remains adamant that Howard University is uniquely positioned to accomplish what eludes even the best schools in this country, if not the world.

“Howard University is a source of so much wisdom, training, and preparation,” King said. “A Harvard could do it, but a Howard can do what a Harvard can’t.”

A Washingtonian to his core, Colbert King has spent a lifetime writing toward the city he loves: its promise, contradictions, and resilience. Ask him to connect the dots — Foggy Bottom kid, Howard government major, soldier and civil servant, banker, then editorialist — and he doesn’t reach for dramatic turns. He simply returns to his “remedial English” experience with Professor Buncombe.

“Writing, writing, writing. It was Howard that recognized [that talent] and nurtured it. End of story.”

Article ID: 2391