The world has never, ever, seen a cultural maven as unique as Deborah K. Allen (BFA ’72, DHL ’93), better known as Debbie. She has broken barrier after barrier in the performing arts, boldly putting not just her own phenomenal talent on display, but those of other artists as well. Whether she is working with well-established performers or those just beginning to step into their greatness, Allen has a singular ability to bring forth what can only be called creative magic.

She is that rare artist who is relevant in any time period. Her first Emmy win, for example, was in 1982; her latest was in 2021, 39 years later. This year, she’ll receive an honorary Oscar for her lifetime of artistry. Generations of multi-talented creatives have used her as a role model, muse, and sensei. She’s taught, mentored, and influenced scores directly and countless more she will never meet.

On any given day, Allen could be called by a multitude of titles — director, actor, singer, dancer, choreographer, producer, author, teacher, or simply superstar. Over the course of a career spanning decades, the consummate professional has been at the center of innumerable cultural phenomena, from her trailblazing starring role in the groundbreaking television and movie hit “Fame,” to her work as producer of the Oscar-nominated “Amistad,” to her turn as director of the iconic HBCU tribute show, “A Different World.” It seems every time Allen has reached the peak of her career, she reinvents herself. There is also another title important to her — Howard alumna. Allen graduated from Howard cum laude in 1971 with a BFA in classical Greek literature, speech, and theatre and was awarded an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree by the university in 1993.

Allen has a reputation for being the definition of a multi-hyphenate entertainer, able to sing, dance, or act on par with any artist in modern history. It’s hard to believe that her path to Howard went through the North Carolina School of the Arts, a college that rejected her. Even though she was used as a model for others during her auditions, she was told she could not attend because she, supposedly, did not have the right type of body for ballet. Earlier, as a child, the Houston Foundation for Ballet had also told her no, before eventually making her the company’s first Black dancer. Both rejections had the tinge of racism. In fact, Allen spent part of her childhood in Mexico after her mother, Pulitzer Prize-nominated poet Vivian Ayers, relocated her children so they could experience life without the racism of the American South. In a full circle moment, the University of North Carolina School of the Arts would eventually award Allen an honorary doctorate for her excellence.

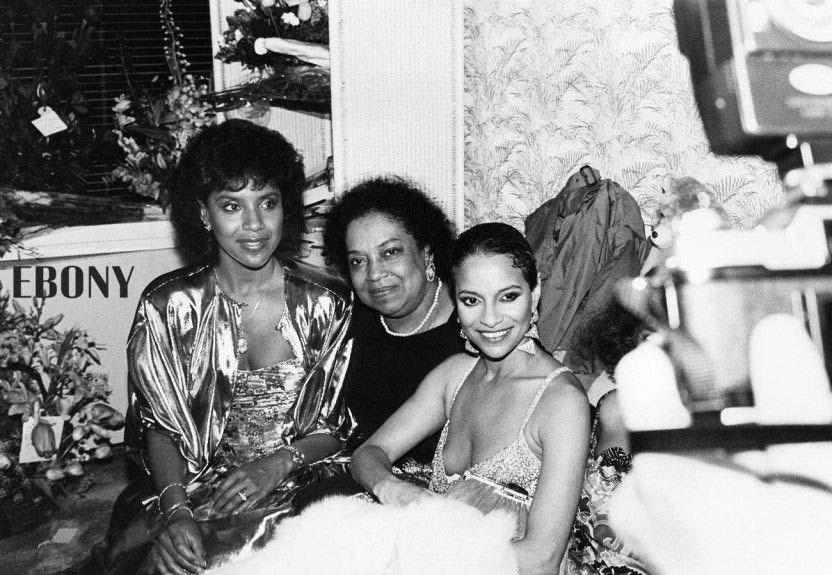

Unlike the other institutions who told Allen “No,” Howard told Allen “Yes.” In coming to Howard as a student, she followed in the footsteps of her father, Dr. Andrew Arthur Allen (DDS ’46) and older sister Phylicia Rashad (BFA ’70), who would become a multiple Tony Award winner, star of television’s number one show for successive years, and dean of Howard University’s Chadwick A. Boseman College of Fine Arts. But younger sister was never one to lurk in the shadows of others. As a Howard student, she set about making her mark on the world in one of the boldest bursts of pure talent the 158-year-old institution has seen. After her experience in North Carolina, Allen had decided to pursue other subject matters at Howard. But performing was something she just couldn’t shake. She went to an event hosted by legendary dancer and Howard instructor Mike Malone (M.A. ’67) and was simply enjoying herself, randomly dancing but using high kicks, twirls, and other forms of ballet and modern dance. Malone noticed her, pulled her aside, and convinced her that she could be a star. The next day, she was in his dance class, and the rest is history.

“Mike Malone saw me at a dance at a party, and he saw me do a triple turn and kick my leg to my face,” she recalled. “He was like, ‘who is that?’ He started talking to me about his dance company and told me that he had been in Dance Magazine. Dance Magazine was a big thing when I was a kid, and I had never seen a Black man in Dance Magazine. He showed me the magazine, and I was like, ‘Wow!’ So the next day I was in rehearsal and never separated from Mike until I went away to New York, and even when I did ‘Fame,’ I brought him to choreograph an episode. He was beyond an inspiration for me and any young person that he touched.”

In fact, as she told the International Choreographers’ Organization and Networking Services (ICONS), Howard provided her first opportunity to act as a real choreographer.

“I was invited to do something in college, at Howard University, in Washington, D.C.,” she told ICONS. “I had been making up little things before, but that was the first time I ever really did something that made me understand what choreography was about.”

It didn’t take her long to make her mark after graduating from Howard in 1971. That same year, she performed in a Broadway production of “Purlie,” based on a book by fellow former Howard student Ossie Davis, and then became principal dancer for George Faison’s Universal Dance Experience. She returned to Broadway to appear in an adaptation of “Raisin in the Sun,” before taking on the role that would define her early career — a principal cast member in productions of “Fame.”

Even as a newly-minted alumna, she inspired Howard students. She returned to The Mecca in 1977 to perform with the Jason Taylor Theatre Movement, garnering a standing ovation in Cramton Auditorium after singing and dancing to “Music and the Mirror” from the hit Broadway play “A Chorus Line,” which she had also performed on the 1977 variety series “3 Girls 3.” As reported by The Hilltop, she called Howard “her greatest experience of growth and her place of maturity.” Much of the versatility, adaptability, and determination she demonstrated in college and thereafter came from values taught to her by her mother, who died this year at age 102. Allen helps others embrace those values in advice she gives to performers.

“The advice that I would give is what kind of came to me in a very hard way from my mom, which is you have to take responsibility for whatever happens and you cannot be the victim,” she said. “It’s about staying in the race because it’s so easy to get out of it. I mean, I stepped off the track after that experience I had at North Carolina. But my mom did not let me have a pity party about what they did and what they didn’t want. She made me responsible. So, I went to Howard and everything turned around. Everything turned around. I had the most incredible professors who are still my advisers, such as Dr. Eleanor Traylor. I had the professors of life all around me and it was a gift. It was like destiny that I was not accepted to North Carolina and landed at Howard.”

Allen starred as dancer Lydia Grant in the movie and television versions of “Fame,” a story about students at a performing arts school, at a time when few Black performers were featured on either the silver or small screens. “Fame” is also where Allen put her directing skills into full gear, choreographing and directing the show’s dance scenes when the actual credited directors proved unable. Her work earned her a Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Television Series — Musical or Comedy and two Primetime Emmy Awards for Outstanding Choreography.

Article ID: 2341