When the University Film & Video Association (UFVA) convened its 79th annual conference at Prairie View A&M University in July, a three-person Howard University contingent took the dais with a charge that felt more spiritual than academic.

Professor and alumna Montré Aza Missouri, Ph.D. arrived with two rising voices, third-year MFA candidate Zion Binet Murphy and graduate Jala Bennett (MFA ‘24) (who works under the creative name Jay Najeeah), to present on “54 Years of Filmmaking at Howard University,” a sweeping look at how generations of Howard filmmakers have shaped, critiqued, and expanded the language of Black cinema.

Missouri had tapped the pair earlier this summer alongside second-year MFA student Christopher Roberts with a simple invitation that carried historic weight — bring Howard’s inimitable story to a national convening of film professors, practitioners, and students.

“It’s a conference for film academics and professors and also filmmakers in academia to come in and talk about the work,” Najeeah explained. In particular, conference participants discussed “where we’re going in academia and where we’re going in Hollywood,” she added.

Three Presentations, One Pedigree

Murphy’s presentation, “Filmmaking from the Heart of the Empire: U.S. Third Cinema’s Impact and Legacy,” mapped how the L.A. Rebellion and the New York cohort of Black independent filmmakers informed contemporary Black film practice, and how that insurgent, community-rooted cinema became a set of methods and ethics that today’s makers continue to refine.

Roberts’ piece tackled the craft side: the Black film aesthetic as a Howard-grown set of cinematographic choices that have leapt from classrooms and student sets into the broader mainstream industry. In lieu of his presence at the conference, a video essay on his thesis screened at Prairie View and later to first-year MFA students back on campus.

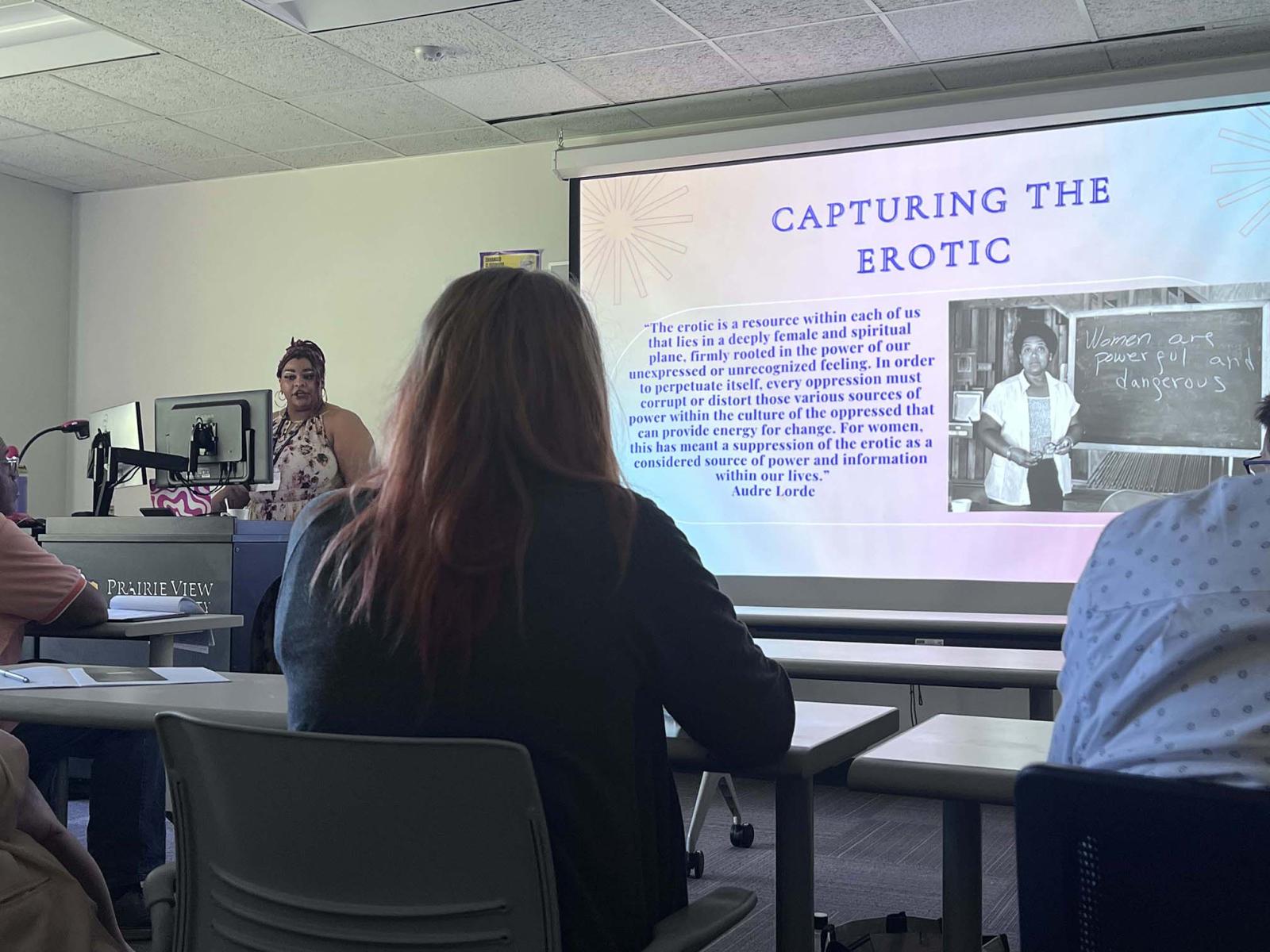

Najeeah’s paper, “Black Queer Cinema, Womanist Filmmaking, and Reframing Our Stories at Howard University,” centered the unmistakable imprint of Black and queer women on the canon, insisting on frameworks that read Black women as subjects, not footnotes.

The papers were designed to course seamlessly. “All the papers flow together,” Najeeah said. “We go from Zion’s historical and theoretical context, to Chris’ lens on the aesthetic we cultivate at Howard and how it branches out, then to my focus on Black women and queer Black women reframing how we look at film.”

The response was immediate and humbling. Elders from the very movements the team were discussing sat in the audience.

“Members of the L.A. Rebellion were there,” Murphy said in awe. Filmmaker Zeinabu irene Davis was among those who took a seat and listened. “You can’t mess that up,” Najeeah remembered thinking. “All these people who made Howard MFA into what it is today were sitting in front of us.”

If the panel had a secret weapon, it was Missouri’s pedagogy — equal parts rigor, care, and clarity. “You should know it, fully,” Najeeah said of Missouri’s expectations. “All the ins and outs and the minutiae. And you need to be able to switch fast: exactly what you’re saying, why you’re saying it, and how it applies to the work.”

That rigor sharpened their writing. Najeeah recalls handing in an early draft and receiving a bracing note back: “center Black women.”

“I’d written to prove I knew the canon, the usual parade of Old-World critics,” Najeeah recalled. “Montre said, ‘You’re not centering Black women in your paper.’ She was right. The rewrite reframed the argument around scholars such as Jacqueline Bobo and a lattice of Black women critics who have long articulated how audiences read, respond to, and repair the images placed before them.”

Murphy learned from Missouri the essence of authenticity. “Be yourself and recognize that’s enough,” he said. “It should be assumed you know the canon, but the point is, what are you adding? What does it mean in your voice, from your place?”

What the students presented in Texas was less retrospective than a living map, and one where nearly every road led back to Howard. Both students keep a running mental roll call of prolific filmmakers who are fellow Bison, such as Arthur Jafa, Bradford Young, Malik Sayeed, Hans Charles, and Ernest Dickerson, to name a few.

“A Black [cinematographer] is, at most, three degrees of separation from Howard,” Najeeah said. “Usually one jump.”

Those connections were palpable throughout the convention. Murphy remembered talking with a professor who had once seen Bradford Young guest teach at UCLA repeating guidance that is heard daily at Howard: Create from your cultural specificity and let the universality emerge from that honesty.

“Outside of Howard, that’s life-changing for people,” Murphy laughed. “For us, that’s Tuesday at 9:40.”

‘We’re Howard, Our Own Thing.’

Since the duo were traveling to a fellow HBCU (Howard has the only HBCU graduate film program in the country), they were especially eager to express how Howard has contributed significantly to the cinema oeuvre, but the pair were still visibly anxious in the immediate lead-up to the session. The stakes were real — not only because of who sat in the audience, but because of what Howard represents when it shows up in national spaces like UFVA.

Najeeah said that their participation at the conference meant that they were “honoring the space, honoring the craft, and honoring the Howard MFA for what it is.”

The conference also underlined a familiar MFA lesson; that theory and practice evolve simultaneously. “We’re getting our MFAs, but we’re also creating the theory as we move,” Murphy noted. The team heard echoes of Missouri’s classroom language at panels halfway across the country, evidence of how far Howard’s ideas travel.

“We’re not a chocolate-covered [University of Southern California],” Murphy added with pride. “We’re Howard, our own thing.”

Murphy speaks like a true auteur: experimental, curious, and allergic to convention. “I want to push the form and show authentic Blackness that can’t be reduced to genre shorthand or trauma,” he said. That means creating films that resist being cataloged as “crime drama,” “struggle narrative,” or any single, flattening register, Murphy explained.

“Use the master’s tools to disrupt the master’s house,” he mused, “Or at least rewire it.”

Najeeah stakes out a similar yet distinct horizon: the Black South, Black women, queer life, and horror as catharsis. “Horror lets you feel what you’re afraid of without it hurting you further,” the pair said. “It’s a way to process the traumas of living in a white world and to meet your whole self.”

Even outside of horror, they chase fullness such as the breath of Black women’s emotions, rage included, without apology. “Women should get to be angry more,” Najeeah said. “Joy, too. The whole range.”

Embrace organized chaos. Build systems, plan as best you can, and then meet the day with flexibility.

Wins, Wisdom, and What’s to Come

That clarity has already borne fruit. Najeeah’s thesis film “Hag” earned the 2024 Focus Features’ Social & Cultural Impact Award and continues an impressive festival run. As of this summer, the film has amassed more than two dozen laurels with screenings still ahead.

Asked what they would tell a first-year Bison filmmaker, both answered with little hesitation. “Do it anyway,” Najeeah said emphatically. “If a risk nags at you, take it. If a professor or peer doubts a choice you believe in, test it on screen. Nothing truly fails but a try, and even then, there are lessons to be learned for future productions.”

“Embrace organized chaos,” Murphy added. “Build systems, plan as best you can, and then meet the day with flexibility. That’s why you rarely see me stressing,” Murphy laughed. “I get my crying out beforehand.”

Both recall the early shoots that taught them to keep moving — shoot around obstacles, lean on community, and make the film anyway. “Learn your craft and cultivate what you want to see,” Najeeah said, describing how they developed a three-hour special-effects makeup look for their thesis and taught it to the artist on set. “Nobody else is doing it, so do it.”

Murphy and Najeeah are effusive about the craft they see every spring in thesis screenings, naming recent projects by peers that dazzled on cinematography, sound, and direction. They are equally candid about what would accelerate the program in the next three-to-five years: trust and resources.

“Trust that we’re good at what we do. We need cameras and lights that work. We need the same belief on paper and in budgets that shows up when we present on national stages,” Najeeah said.

Even in making these recommendations, they insist the measure of Howard is in what makes it different. “We shouldn’t be judged by someone else’s metrics,” Murphy says.

“Our alumni already changed film.”

Article ID: 2376