The undergraduate enrollment and graduation rates of Black males have long been points of consternation in higher education.

A 1989 Washington Post article headlined “Black Males Increasingly Rare in College” openly fretted over the dearth of the population on university campuses across the country, citing an American Council on Education study that accordingly described Black males as “disproportionately at risk in American society.”

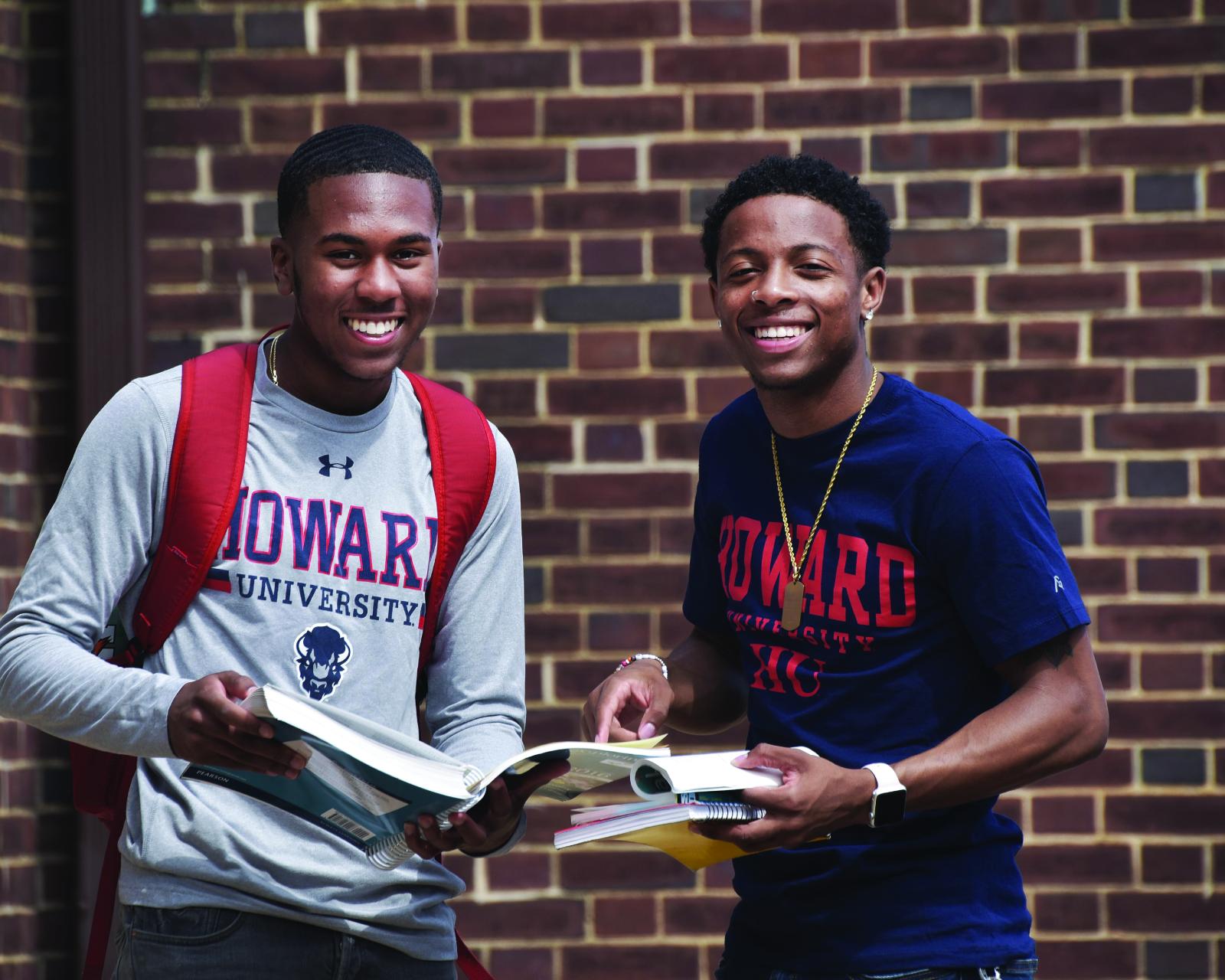

Yet, contemporary articles from the same publications underscore how little has changed. Per the Postsecondary National Policy Institute, Black men represent just 4.6% of all postsecondary enrollment, or just over 850,000 of the nation’s 18.6 million college students. These numbers can feel particularly acute at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) such as Howard University, where the female-to-male ratio is approximately 3-to-1, according to the University’s fall 2022 campus census.

The Numbers Behind the Story

Modern data makes a persuasive, if practical, argument that Black males are not pursuing postsecondary education at high rates simply because many are not graduating from high school. The most recent Schott 50 State Report on Public Education and Black Males, released by the Schott Foundation for Public Education in 2015, reported that national public high school graduation rates were 59% for Black male students in comparison to 65% for Latino males and 80% for white, non-Latino males. Although the COVID-19 pandemic precipitated school districts nationwide relaxing their graduation requirements, whether these students are truly prepared for tertiary education remains a concern.

The statistics only continue to paint a grim picture. The National Student Clearinghouse published that Black male undergraduate enrollment decreased by 14.3% between March 2020 and March 2021. The United Negro College Fund (UNCF) recently declared that Black men have the lowest college completion rate at 40%. A 2021 Education Trust investigation into 2018 U.S. Census Bureau data uncovered that only 26.5% of Black men held a college degree compared to 44.3% of white men.

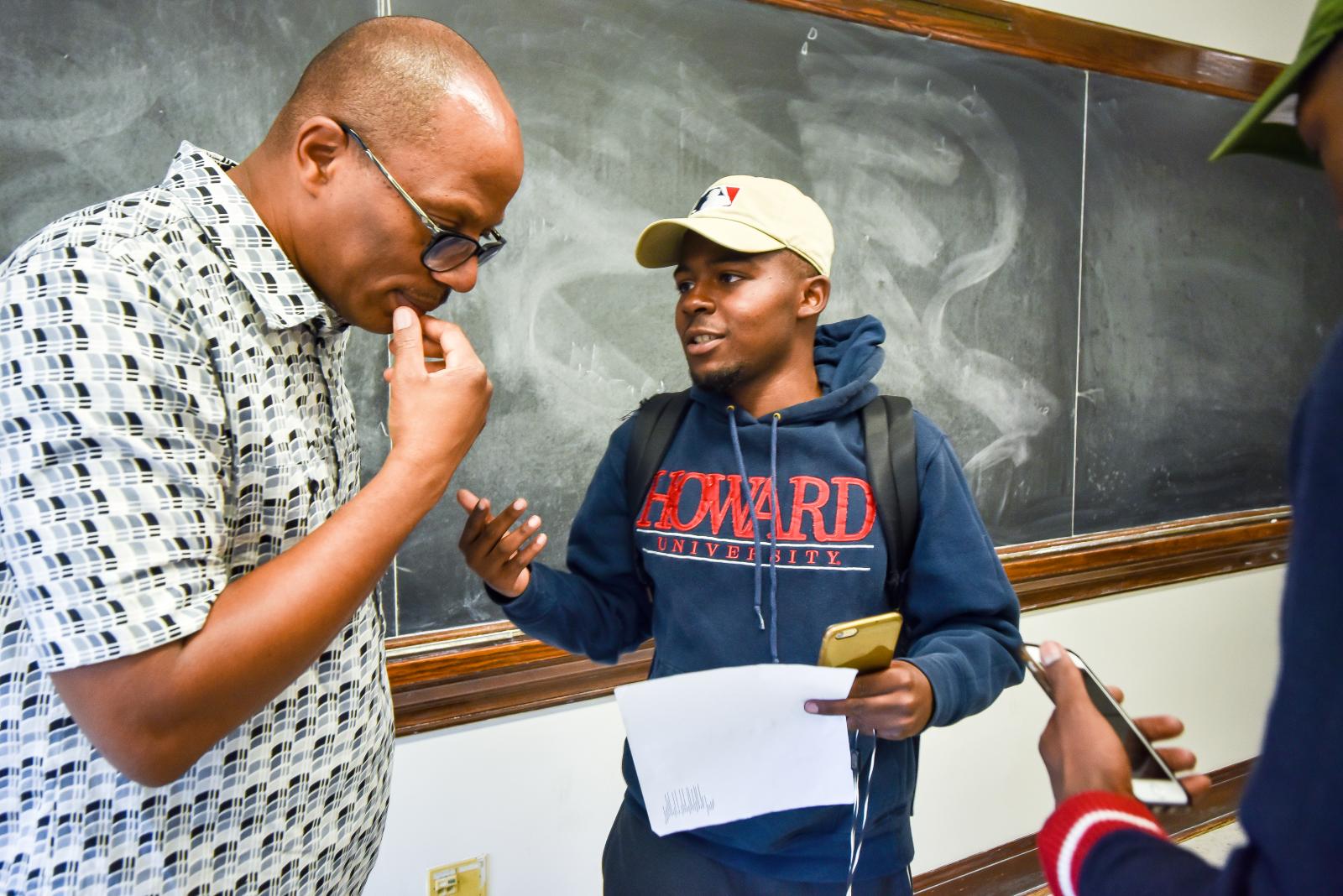

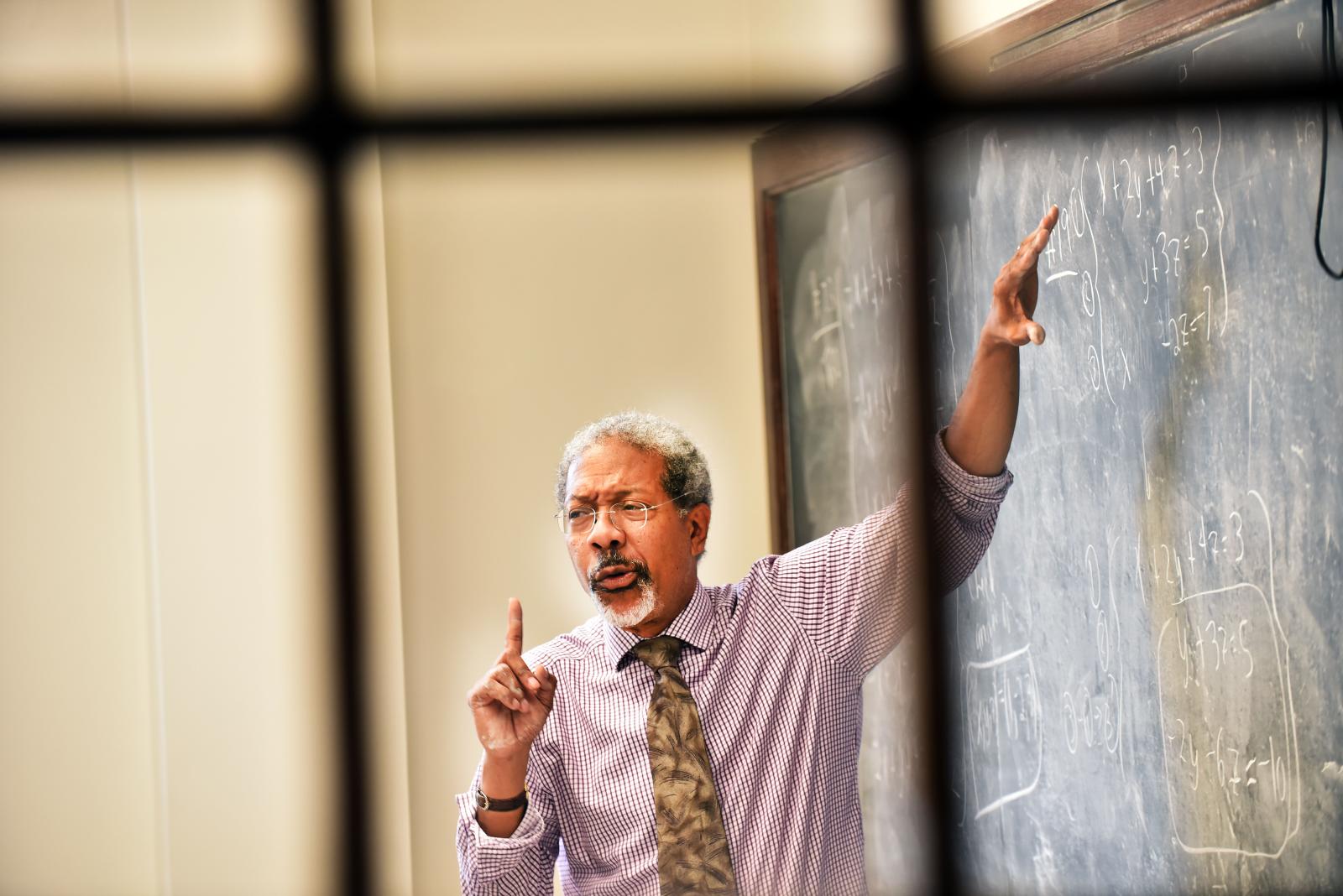

The good news is that select schools like Howard have reported historic increases in their male application, enrollment, and graduation rates. For the academic year 2022-23, the University received 9,705 male first-time-in-college (FTIC) applications, well over triple the amount collected a decade earlier. In fall 2022, the University enrolled 2,758 male students, a 17% growth from fall 2013 — and a 31% bump from fall 2019. The University’s four- and six-year graduation rates for males have likewise trended upward over the past 10 years.

Jarrett Carter Sr., director of operations, strategy, and communications in the University’s Office of the Chief Operating Officer, attributes the boost in male interest to Howard’s metropolitan location, its breadth of degree programs, and its inclusive environment. “These are the mechanisms we have in place for every Howard student, and there are elements of the ecosystem that in direct and indirect ways look to contribute to male achievement,” Carter says.

“We are trying to buck historic trends,” Carter continues. “While we may not be able to recruit by race or gender, we still want Black males to know that Howard University is a place where they can succeed.”

Article ID: 1401

Keep Reading

-

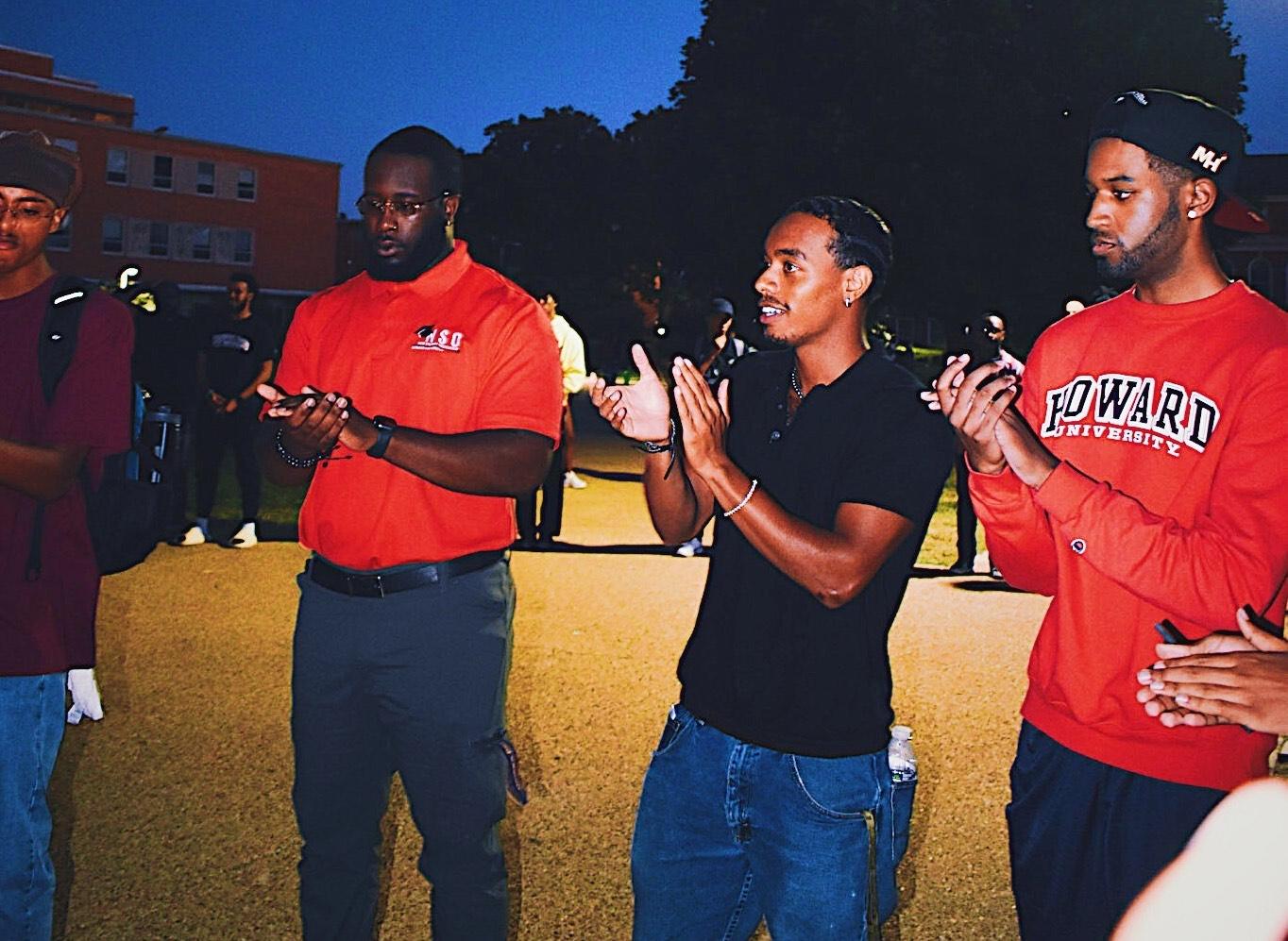

Men of the Mecca Initiative

Men of the Mecca was designed to identify the unique needs of the Black male population and create an infrastructure of support around them.