Recent graduate Becca Haynesworth (B.A. ’25) has continually served in many roles, from community leader to filmmaker, digital strategist, and farm apprentice. Coming to Howard University in 2022 allowed her to explore a new identity — that of a writer.

“I would sneak in my passion for writing through the media work that I would do, whether that would be writing scripts or actual academic research on media. I was always trying to infuse my passion for writing, but it wasn’t in the right space,” she said. After transferring to Howard, Haynesworth began working with the student-run political journal The Liberato and joined the Kwame Ture Society for African Studies.

“When I stepped into these spaces, it was very affirming. It allowed me to expand and better connect with the legacy,” Haynesworth said. During her senior year, Haynesworth — encouraged by friends and English professor Darlene Taylor — joined The Amistad, Howard’s literary journal.

Named in honor of the 53 slaves who revolted against their captors aboard La Amistad in 1839, the journal’s mission is to “elevate the creative voices of the Black diaspora through poetry, fiction, interviews, and visual art.” Since its reformation in 2018 after an initial end to its production in 2010, The Amistad has been dedicated to publishing both emerging and established writers. Run entirely by Howard undergrads, the journal brings together not only writers but students of all backgrounds. At the same time, its editorial staff and volunteer club learn about every step of the publishing process.

Previous issues have featured groundbreaking writers such as Roxane Gay, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Jesmyn Ward, and A. Van Jordan. In the Spring 2025 issue of The Amistad, the editors shifted the focus back toward students, a move that held special significance as they —along with the rest of the campus — dealt with the political turmoil of the past year.

“For this issue, we wanted to see what student voices are saying about what we’re seeing in the world, since that can often be overshadowed [because] we’re students,” said rising junior and fiction editor Olivia Ocran. “We also want to bring to light this conversation about Black people’s place in this country and how we are seen politically.”

This desire to spotlight Black people’s and Howard students’ place in the current moment led to the latest issue’s theme: revolution. The works published — whittled down from 126 submissions, a record for the magazine — revealed just how broad the word “revolution” can be. Through poems, essays, and short stories, the writers explored topics such as racist policies, colonialism, climate change, and banned books. They also looked back with love on their mothers and their grandparents; contributors wrote about drawing strength from community in churches and jazz clubs and about learning to love their own hair.

“Us being able to have these conversations in the first place is an act of revolution, and we really wanted to showcase that,” Ocran said. “We didn’t say the word revolution [to mean] just fighting and protest. We also wanted the little victories in life.”

Connecting Writing to the Real World

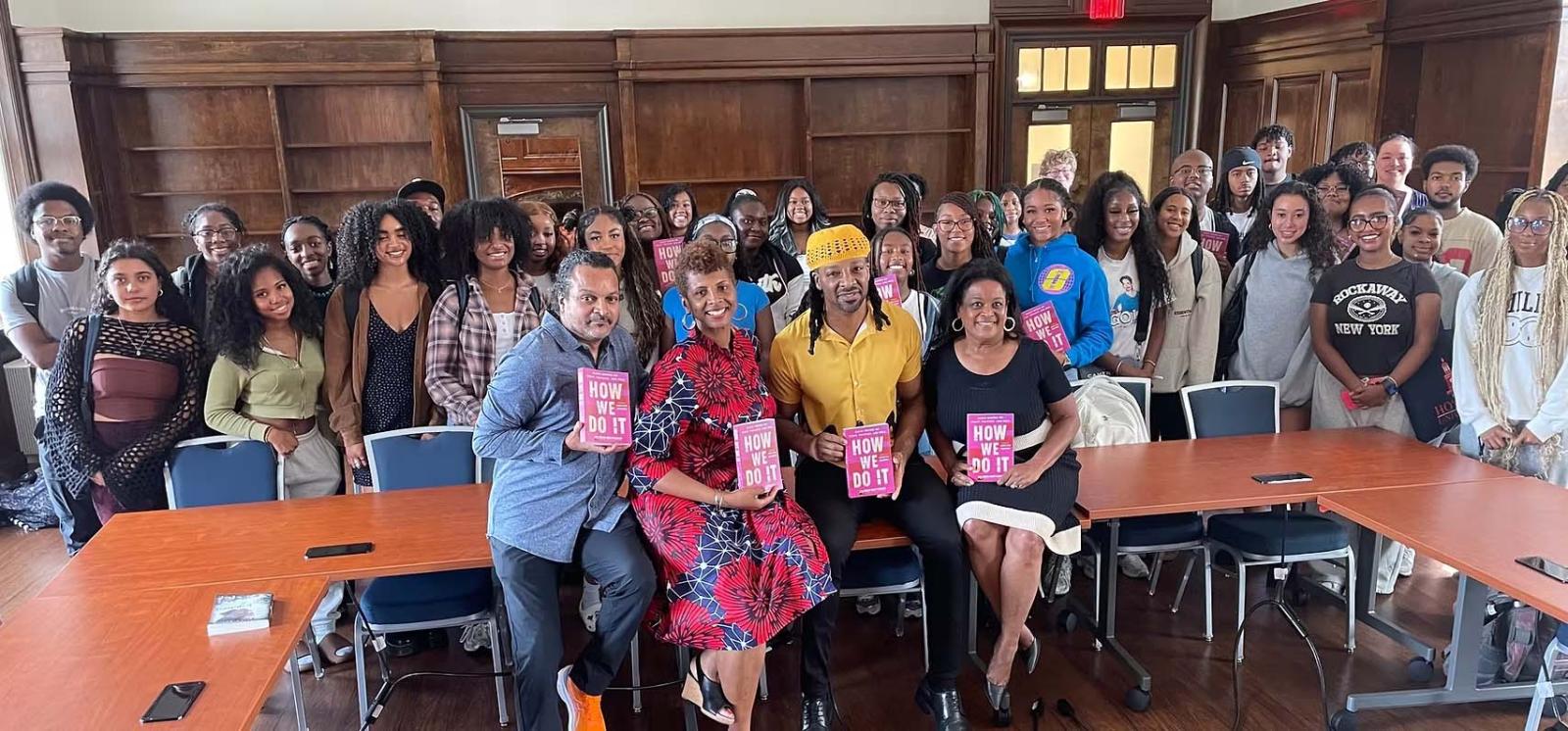

One of the most important aspects of The Amistad club has been the guest speakers, brought in by Dr. Taylor. Guests have included Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Jericho Brown, industry professionals, and Howard professors.

“We had a lot of guest speakers that opened [students’] eyes to different ways to work in the literary world,” said Ocran. “You don’t have to just be a writer. Some of them were writers and agents; they were working with writing organizations and with nonprofits. They were professors and teachers. They were doing all these things at once. We don’t have to box ourselves into one thing.”

The speakers reflect a broader shift happening within Howard. Under the leadership of Dr. David F. Green Jr., associate chair of writing, faculty are working to expand how they approach writing courses. Current courses are being updated to directly tie rhetoric to students’ everyday lives and place it in a broader historical context.

“I want students to leave my course with something useful, something they can put in a portfolio, something you could talk about on your resume, a skill set,” said rhetoric professor Ja’La Wourman, who began teaching at Howard in 2024. Wourman added that she’s aiming for students to gain “a better understanding of [themselves] and how the world around [them] is creating messaging. I want my students to leave with an understanding of that rhetoric that’s happening without them knowing and how some things have not always been in the favor of Black Americans, but that can be a part of change, whatever field they’re in.”

The department is also taking steps to continue upholding Howard’s legacy as a pillar of literary history. This includes a recent vote to change its name from The Department of English to the Department of Literature and Writing, a name more accurately capturing the breadth and impact of the department’s focus and the range of cultures and literature stuidied. There are also plans to establish a low-residency MFA, the culmination of more than two decades of work by Creative Writing Director Dr. Tony Medina. To him, Howard and the Writing and Literature Department owe it to students to connect their work to the real world.

“You can’t expect Black students to come into the classroom, block out the world, scribble on a piece of paper, and ignore what’s happening and not let them express themselves,” Medina said. “You go to other universities and colleges, and they [may] never have a conversation about what’s happening in this country with regards to racism, what’s happening in Palestine, or what’s happening in Ethiopia or Haiti. At Howard, we’re having those discussions in the classroom.”

To Haynesworth, this connection to the real world is what made writers like Zora Neale Hurston (A.A. ’1920) so impactful. “You can’t talk about the Black literary tradition without talking about Zora Neale Hurston,” she said. “She was the keeper of memory. Beyond a researcher, [Hurston] was doing liberatory work as far as making Black people understand that their connectivity to Africa is nothing to be ashamed of.”

Haynesworth is currently part of a project to preserve Gullah Geechee culture in the Southeast, often researching in the same place Hurston once did. In this way, she — like The Amistad — is continuing Howard’s long literary legacy.

Article ID: 2436