I wanna live good, so sh*t I sell dope

For a four-finger ring, one of them gold ropes

Nana told me if I passed, I’d get a sheepskin coat

If I can move a few packs, I’d get the hat – now that’d be dope.

That’s how Curtis Jackson, more famously known as 50 Cent, wistfully reminisces on the style of burgeoning hip-hop culture from his vantage point in 1980s Queens, New York, on the 2005 classic record “Hate It or Love It.” Four-finger rings. Chunky gold chains for the fellas and door-knocker nameplate earrings for the ladies. Adidas shell-toe sneakers. Between LL Cool J and Run-DMC, Def Jam Recordings may have singlehandedly been keeping the Kangol brand in business. To be certain, the fashion was gaudy, but when you want to establish yourselves as a cultural institution, one doesn’t have much time for subtlety.

As hip-hop bulldozed its way into the mainstream in the 1980s, it did so with flair and panache, carving out an early identity around individual liberty and artistic expression that would make it impossible to ignore.

The fashion in other cultures generally trended more conservative during the Ronald Reagan era, but hip-hop icons were showing and proving that business suits, power ties, and the King’s English were not elemental to American success.

“We were always taught in school ‘dress for success’ meant something else, and here they were breaking all the rules and winning,” reflected fashion designer April Walker in “Fresh Dressed,” a 2015 documentary on the evolution of streetwear. “I just remember that changing my life in the sense of, everything I’d been taught was a farce for me from that point.”

...Their own unique way of wearing something came to be a way for people to be distinct, to be identified in a crowd, to stand out.”

Fake It ’Til You Make It

Nevertheless, the grandiose fashion belied the solemnity that often undergirded the music specifically and the culture more broadly, much in the tradition of their predecessors. Just as the flamboyant popular disco and rhythm and blues entertainers of the 1960s and ’70s – acts like Little Richard; Earth, Wind & Fire; and the Isley Brothers – hip-hop’s pioneers embraced their fashion choices as an additional means of connecting with their audiences.

“If you go through the history of African American culture – particularly in the 20th century – style, fashion, clothes were always a very prominent part of people’s identity,” says Todd Boyd, PhD, a hip-hop expert and professor of cinema and media studies at the University of Southern California who goes by the moniker “the Notorious Ph.D.” “Even for people who maybe didn’t have money, their own unique way of wearing something came to be a way for people to be distinct, to be identified in a crowd, to stand out.”

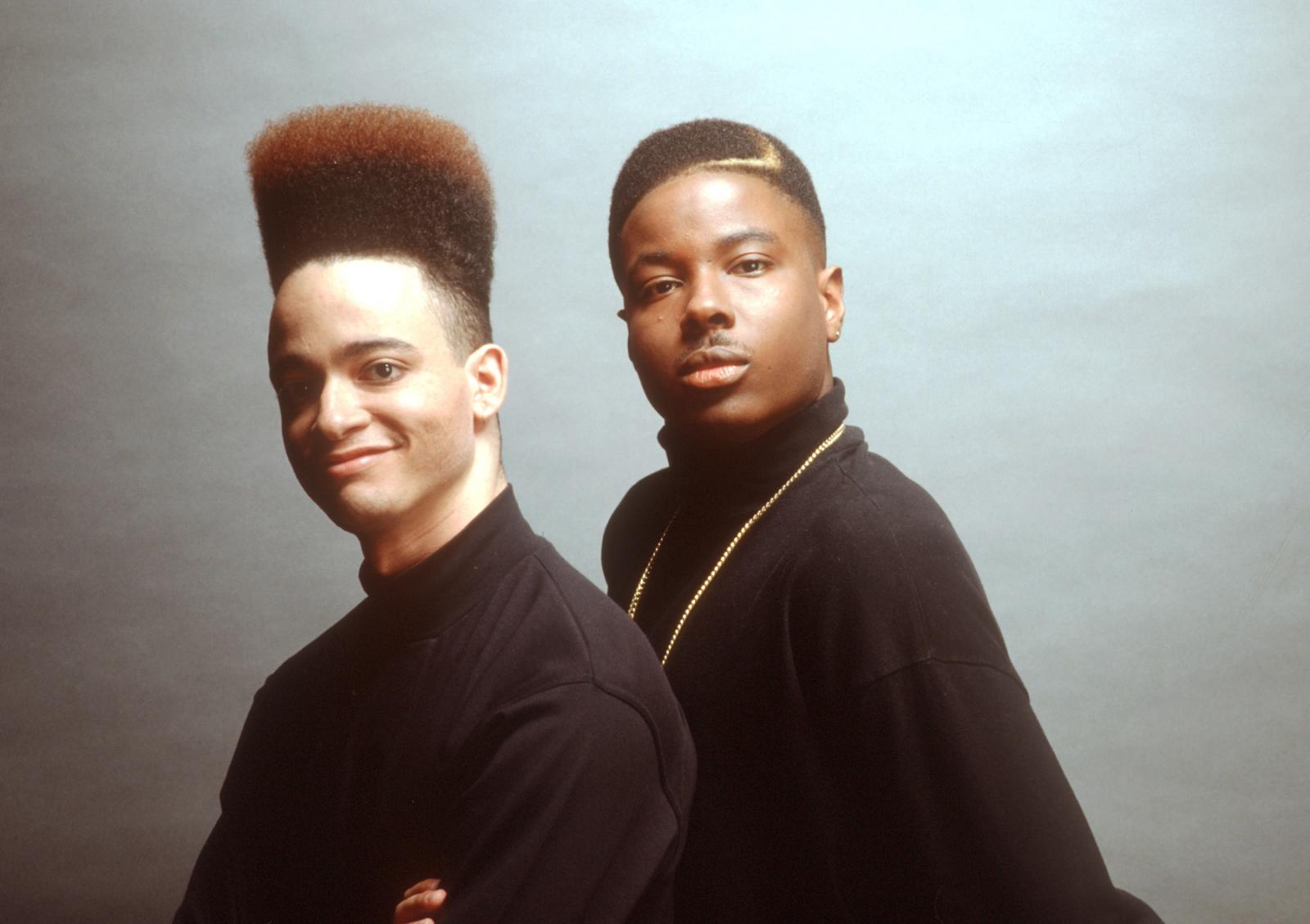

Fashion also became a way for folks to affect a greater socioeconomic status in the face of their actual circumstances. In other words, fake it ’til they make it. In “Fresh Dressed,” hip-hop duo Kid ’n Play laugh about wearing high-quality apparel despite having no money between them, while Roc-A-Fella Records founder Damon Dash describes fashion as “a status symbol based on insecurity.” Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five ironically donned some of their finest threads while documenting the struggles of inner-city living in their video for 1982’s “The Message.”

Author and former Howard adjunct professor Adrian Loving (BFA ’93) discusses this phenomenon with photographer Janette Beckman in his book “Fade to Grey: Androgyny, Style & Art in 80s Dance Music.” In 1982, Beckman began shooting images of hip-hop culture, and counts names such as Run-DMC, Salt-N-Pepa, and Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five among her portfolio. Beckman hails from the United Kingdom, but she quickly understood the significance behind these Black American artists choosing to showcase their earnings. “It was definitely about, ‘I can afford to have gold chains and gold teeth to show you that I’m doing well,’” Beckman says. “All the flashy gold and cars showed affluence and wealth for those artists.”

Loving elaborates on Beckman’s observation. “I think in the Black community it’s like the concept of Sunday best. Even if you’re poor, you will wear your best suit or threads to important things on Sunday,” he says. “For these rap guys to take a toothbrush to their sneakers and keep their gold flashy, and jeans and suits pressed, it’s the same inherent quality as the Sunday best types. They would be looking great on stage and you know momma would be proud of them.”

Hip-Hop in ’80s Television and Film

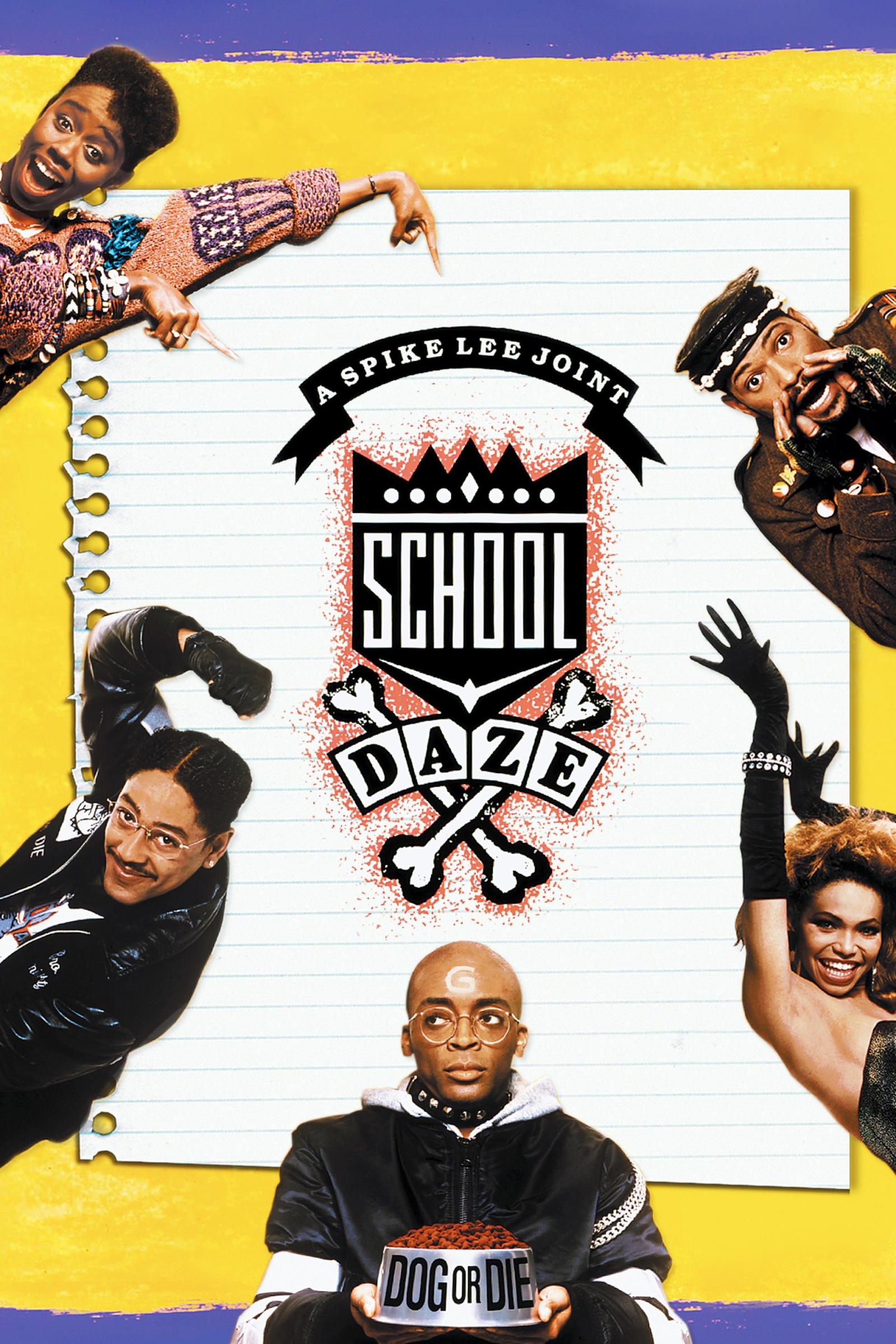

But the style of the era wasn’t limited to opulence, nor was the culture’s distribution limited to the music business. It even began permeating the television and movie industries through filmmakers like Spike Lee. His second film, 1988’s “School Daze,” was a cinematic exploration into student life at historically Black colleges and universities based on Lee’s own experiences at Morehouse College. Although the movie’s soundtrack wasn’t rap-heavy, it did prominently feature the D.C.-based go-go band E.U. and its song “Da Butt,” which

would reach number-one on the Billboard Hot Black Singles chart and the top-40 on the Billboard Hot 100.

“You can’t have this conversation without starting with Spike Lee’s ‘School Daze,’” says Tia C. M. Tyree (PhD ’07), professor in Howard University’s Cathy Hughes School of Communications. “I think for most people, this was the moment where they understood that HBCUs were different spaces, that HBCUs had a culture in and of themselves, and that they were spaces where you not only learned in the classroom, but you learned outside of those educational spaces.”

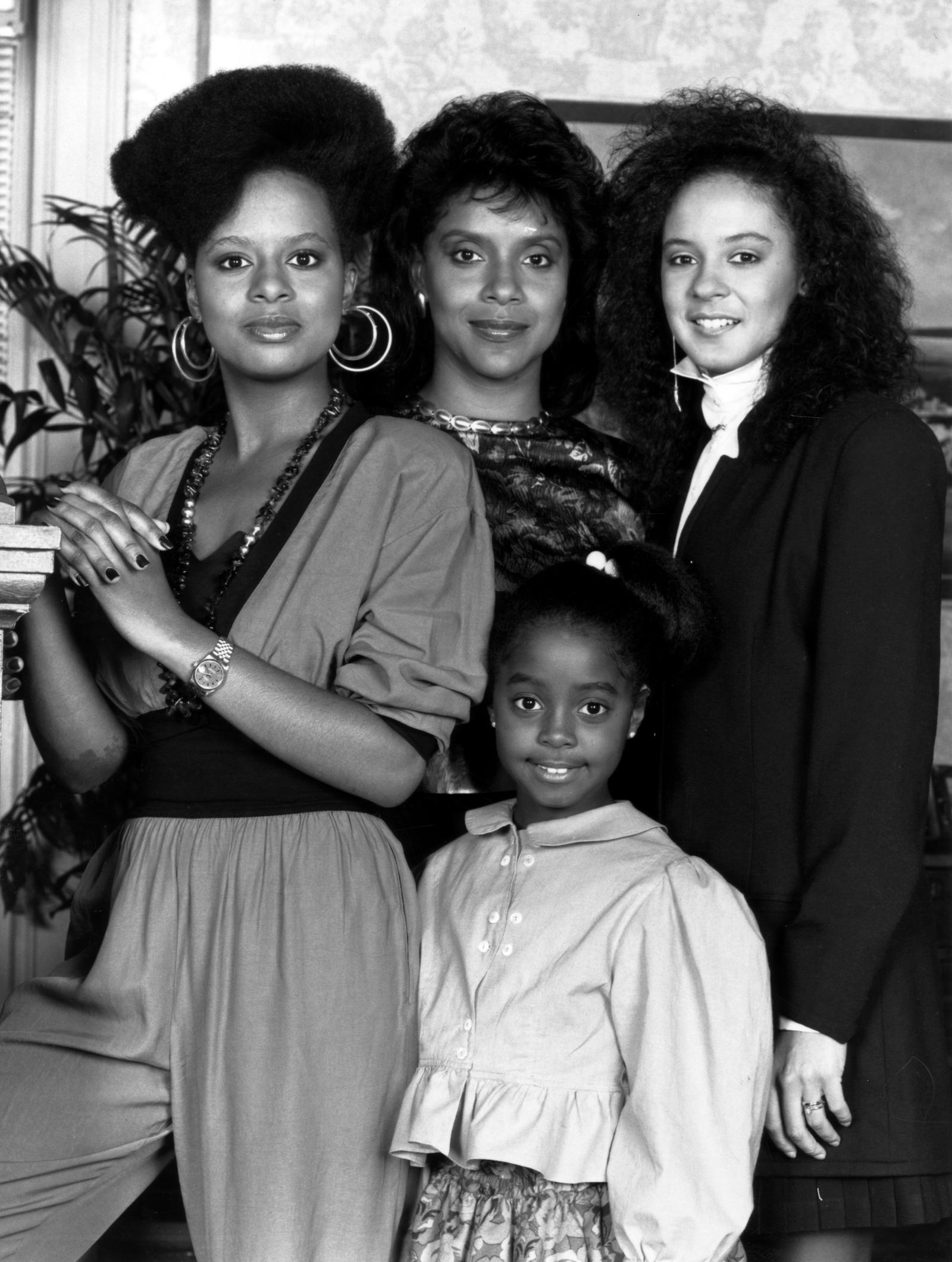

Meanwhile on the smaller screen, the Huxtables out of Brooklyn, New York, were being coronated as America’s first family of the decade. Helmed by matriarch Clair Huxtable, portrayed by Howard alumna and dean of the Chadwick A. Boseman College of Fine Arts Phylicia Rashad (BFA ’70), the family’s five children were coming of age just a couple boroughs over from hip-hop’s birthplace of the Bronx. Malcolm-Jamal Warner’s Theo was the sibling most obviously influenced by the culture, but in “The Cosby Show” spin-off “A Different World," oldest sibling Denise — performed by Lisa Bonet — enrolls in the fictional HBCU Hillman College, which would become the avatar for the Black college experience for millions of households nationwide. (“School Daze” released during the first season of “A Different World,” with both projects featuring Kadeem Hardison, Jasmine Guy, and Darryl M. Bell.)

By the end of the decade, Black disenfranchisement had become the main narrative, and new, socially conscious artists such as Public Enemy and KRS-One were addressing it directly and unapologetically by weaving themes of Afrocentrism into their music. These sentiments of empowerment and self-determination proved popular inside the culture, especially by those embittered by the era’s politics.

These tensions ultimately came to a head on Howard’s campus.

“The Revolution Has Been In Effect”

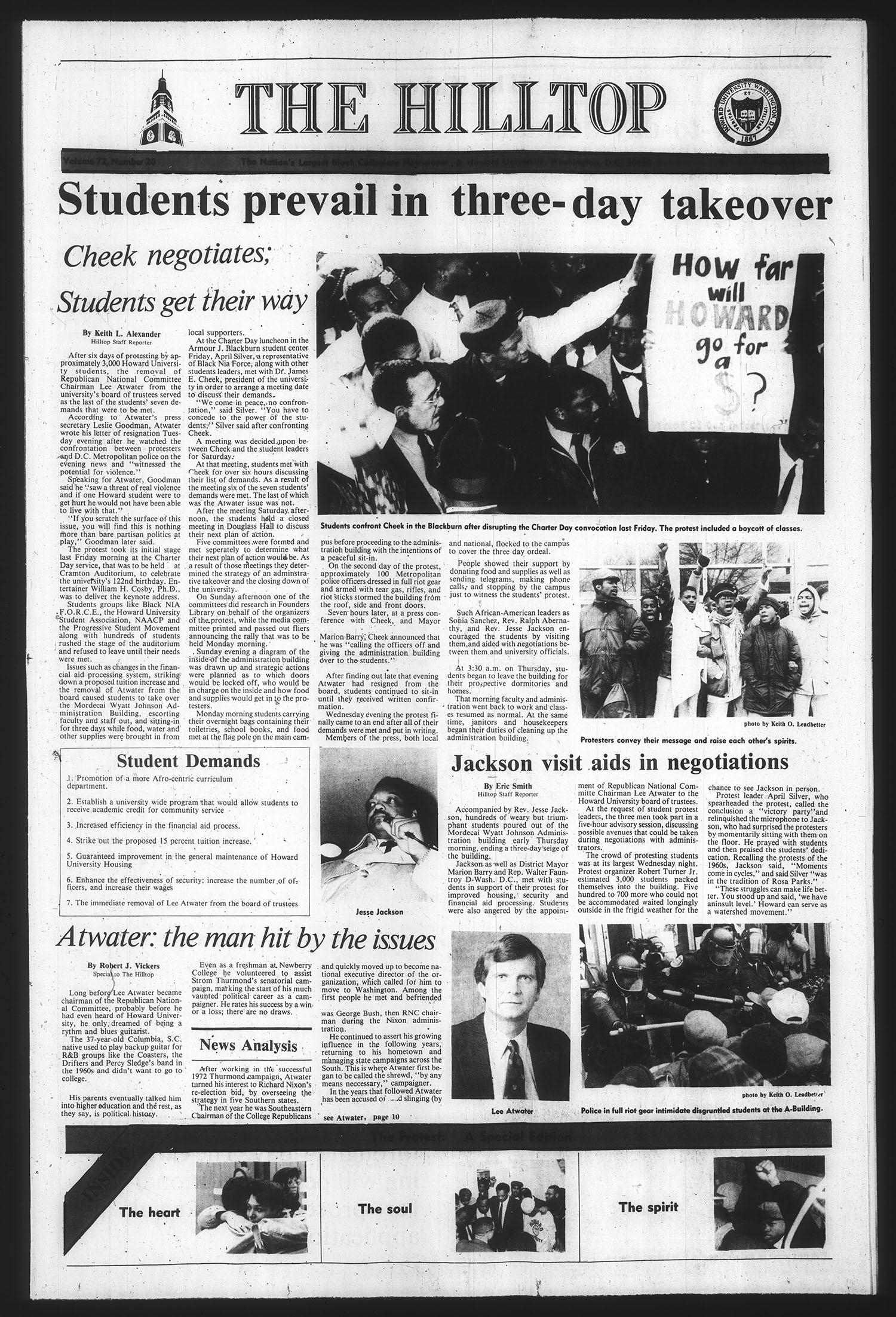

During the 1989 spring semester, Howard University students led by the student organization Black Nia F.O.R.C.E. – an acronym for “Freedom Organization for Racial and Cultural Enlightenment” – protested the school’s appointment of Republican strategist Lee Atwater to its Board of Trustees, culminating in a three-day occupation of the University’s main administration building. Atwater had been the mastermind behind a number of racist campaign tactics for years, most recently employing those tactics as campaign manager in the 1988 United States presidential election. Students attached Atwater’s association with Howard with a dereliction of the University’s Afrocentric founding and mission.

[We] knew that we were clearing a path for future generations of student activists, but we didn’t have a clear sense of just how deeply we had impacted the culture.”

“You have the sense that, if a university has enough of an impetus to select Lee Atwater, then it also is redolent of a university that doesn’t necessarily see African American studies as a discipline that should be supported with more faculty and a center for the study of Africana, a graduate program, these kinds of things,” said Joshua M. Myers, PhD (BBA ’09), associate professor of Africana studies at Howard University, in a 2020 interview on “The Kojo Nnamdi Show.” Myers is the author of “We Are Worth Fighting For: A History of the Howard University Student Protest of 1989.”

Black Nia F.O.R.C.E. was headed by alums April R. Silver (BA ’91) and Ras J. Baraka (BA ’91). Silver is now a communications and marketing executive, and Baraka is the 40th and current mayor of Newark, New Jersey. “[We] knew that we were clearing a path for future generations of student activists, but we didn't have a clear sense of just how deeply we had impacted the culture,” Silver says.

Myers attributed hip-hop as the stimulus for Black Nia F.O.R.C.E.’s dynamism. “It is the hip-hop generation’s answer to Black Nationalist tradition,” he said. “They took the energy of hip-hop and they translated it into political organization. And everything that you would expect from hip-hop and everything that you would expect from the tradition of Black nationalism was crystallized into this one organization.”

Silver confirms this. “Hip-hop was a critical tool for us. We used the culture to start conversations and debates, and to help us do social justice and community-building programs on campus and in the surrounding neighborhoods of Howard,” she says. One “letter to the editor” in the March 17, 1989, edition of “The Hilltop” references the words of Public Enemy directly. “To those critics who feel that this ‘revolutionary thinking’ among students is just a fad that will soon pass,” wrote Stewart Calloway of student organization Black United Youth, “to paraphrase Public Enemy, ‘The Revolution has been in effect – go get a late pass!’”

Howard University’s immediate past president Wayne A. I. Frederick (BA ’92, MD ’94, MBA ’11) was a first-year undergraduate at the University at the time. “Regardless of where you aligned on the political spectrum, I think it was an informative moment for our student body about the power of getting involved and how our voices could be agents of change, even as teenagers and young adults,” he says. “Many of our classmates were literal children of the civil rights movement of the 1960s, so for many of us, this was our moment to walk directly in their legacy.

“When I implore today’s students to make their voices heard, it is because I have seen and felt the impact firsthand, as both a student and an administrator,” Dr. Frederick continues. “Howard University attracts passionate students for a reason, and my cohort was no different. And many of us were certainly emboldened by some of the music and messages of the era.”

In just a decade’s time, hip-hop was established as a dominant cultural force: aspirational enough to explain its mainstream appeal, yet conscious enough to activate social movements across the globe. The grandeur that defined the early ’80s gave way to a more austere side of the culture by the decade’s end, but never fret, dear reader – it only gets shinier from here. Another Howard alum is on the way to make sure of it.

Article ID: 1686