If you checked the rhymes booming from speakers whizzing by the Yard during the golden age of hip-hop, the eclectic mix included political rap, party anthems, New Jack Swing, Native Tongues vibes, Miami bass, Southern rap, and West Coast G-funk – flavor in your ear that was also represented by Howard’s diverse student population.

This period of unparalleled creativity stretched from the mid-to-late ’80s to the mid ’90s, and was punctuated by boom bap beats, masterful emcees, dope dance moves, fresh fashion, and Afrocentric flair (“Black medallions, no gold”). On TV, hip-hop and Black culture wove its way into the mainstream and must-see TV. People watched Denise Huxtable’s matriculation at the fictional HBCU Hillman College on “A Different World,” rap acts made their primetime debut on the “The Arsenio Hall Show” and the sketch variety show “In Living Color,” Will Smith flexed his acting chops on “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air,” and Martin Lawrence made audiences laugh out loud with his sitcom “Martin.” Even Nickelodeon catered to younger hip-hop fans via “All That” and its spinoff, “Keenan & Kel,” with the latter’s theme song courtesy of Coolio. Simultaneously, America saw video footage of Los Angeles policemen brutally beat Rodney King and the “City of Angels” burning after the officers were acquitted; Anita Hill testify against Supreme Court justice nominee Clarence Thomas; and the Million Man March take place on the National Mall. Hip-hop’s messages and soundscapes evolved with the times to reflect the nuances of the new decade.

April Silver (BA ’91) was a student activist, former president of the Howard University Student Association (HUSA) and co-founder of the Cultural Initiative, which in 1991 launched the first national hip-hop conference held at a college or university.

Decades later, the Brooklyn native is still inspired by “the spirit and the essence of hip-hop that taps into a people’s will to survive on their own terms, using their innate style.

“To be so bold and unstoppable is what inspires me 100% of the time,” says Silver.

Howard is Where Hip-Hop Lives

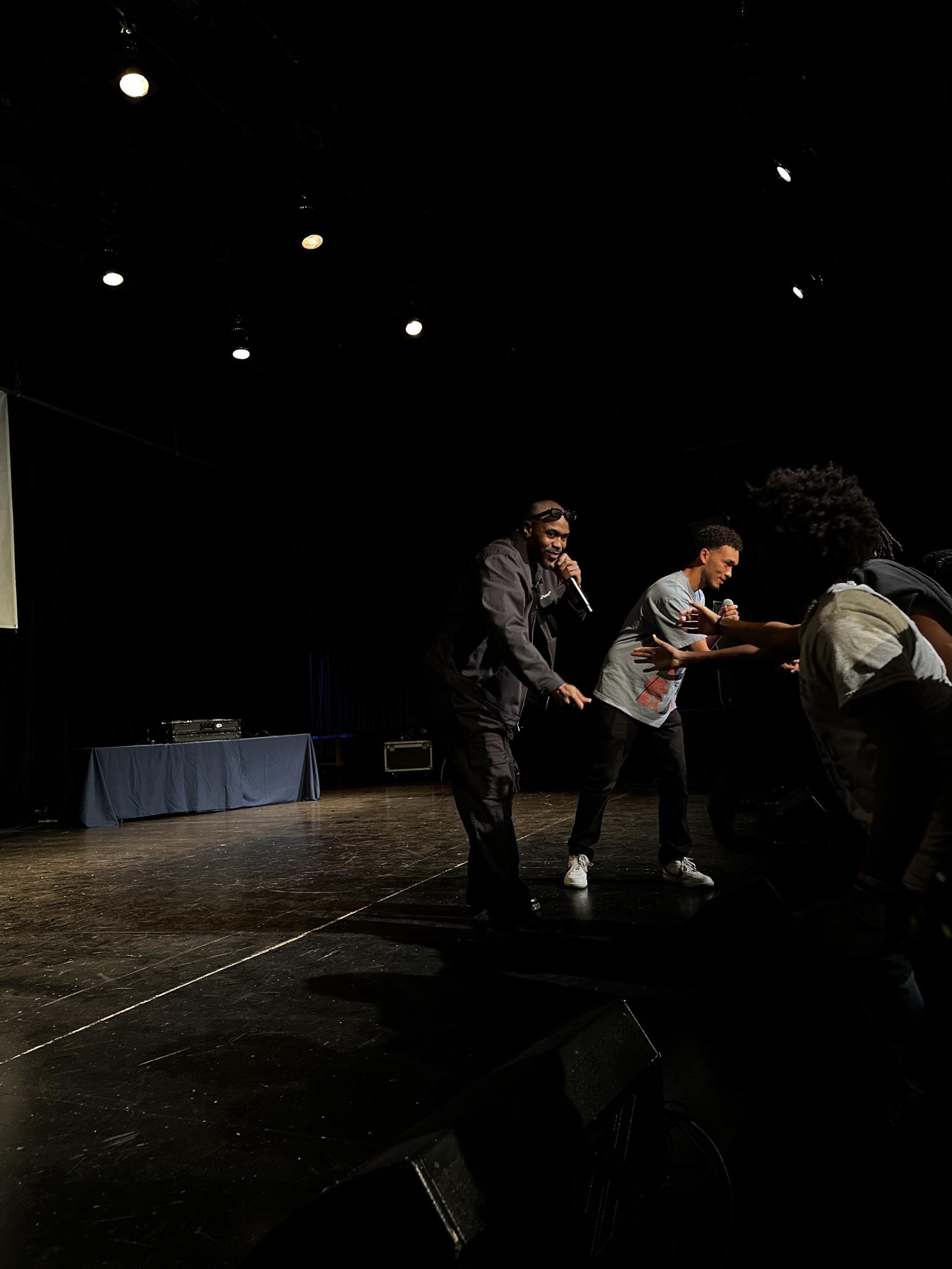

During the ’90s, Howard’s campus and Homecoming was at the center of where hip-hop culture was cultivated, celebrated, and captivated an audience.

Alumni trustee Chris Washington (BA ’92) honed his deejay skills at the student-run radio station, WHBC, and worked his way up from on-air host to general manager. At the time, Howard’s commercial radio station WHUR primarily played R&B music, and the format didn’t change to include classic hip-hop until 2008.

[In the ’90s] Howard as an incubator for people who were trying to make it in entertainment and hip-hop music.”

The Bronx, New York native, whose deejay moniker is “The Legendary Chris Washington,” asserts that since rap wasn’t in heavy rotation on D.C. radio, WHBC was a hot promo tour stop for artists like Salt-N-Pepa, MC Lyte, Kwame, Special Ed, and Third Base.

“We cultivated a space where people could come and their music was played,” says Washington, who fostered relationships with music artists and record labels. He notes that when Sony Music started an intern program, their first interns had worked at WHBC.

Rapper and entertainment lawyer Tracey Lee (BA ’92) agrees that Howard was a great litmus test.

“I don't think Howard gets enough credit for its contribution to the culture. [In the ’90s] Howard was an incubator for people who were trying to make it in entertainment and hip-hop music,” says the Philadelphia native.

“People came from Texas, Chicago, Las Vegas, and all over. So what better place to test, market your material, your product? And it wasn't just music, it was fashion, art, dance, and it was everything intelligentsia.”

Where I’m From

New Yorker Lance Williams attended Howard in the ’90s, and he got a culture shock when he arrived at Drew Hall and saw a foot locker with a Compton address. But despite their different area codes, the Long Islander said he and his roommate became fast friends.

“We put each other on to music from our hoods, and I became a DJ Quik fan because of him,” he says.

For some students, however, being from the West coast was a barrier to fitting in.

Toni Blackman (BA ’90, MA ’94) is from the San Francisco Bay-area and was drawn to The Mecca to be immersed in Black excellence.

Back home, Blackman was part of a respected female rap crew, but she didn’t receive the soul-clap welcome she expected at a talent show her freshman year.

“As soon as they said I was from California, they started booing. And to make it worse, I was wearing white cowboy boots, white jeans, and a pink jacket. It was the antithesis of the New York style. So I got booed twice,” she says.

“At that time, hip-hop was awkward because of regionalism. One, I'm a girl, and two, I'm from the West coast. So anything I wanted to do with hip-hop was met with resistance by New Yorkers.

Eventually Blackman found her tribe and became a fixture in the D.C. creative scene. In 1992, she formed a hip-hop theater ensemble called the Hip-Hop Arts Movement (HHAM) and recruited Howard students who would later blow up in their respective fields, including scholar John Lester Jackson (BA ’93), Step Afrika founder Brian Williams (BBA ’90), and former BET and MTV personality Ananda Lewis (BA ’95).

Lewis, a fellow Californian, fondly remembers working with Blackman.

“That [time] was about music and art. And what art has always done is move the culture forward and allow it to be seen and heard. [Toni] was so creative and so inspiring for all of us,” she says.

The Los Angeles native adds, “Howard was everything. It was about finding myself in an environment where people looked like me and were about the same thing.”

For the Culture

All fashion came from what we wore in the streets. It was a reflection of how we lived and the music we listened to.”

In 1991, the Hip-Hop Conference was introduced at Howard and brought stars, execs, and more to Howard’s campus to discuss the music and the industry. A highlight of the conference was the Hip-Hop Fashion Show. Proudly representing Queens, New York, Jennifer Gumbs (BA ’96) was the show’s fashion coordinator for a few years. She recruited Howard students and D.C. locals to model fresh gear from streetwear brands like Karl Kani, ENYCE, FUBU, Baby Phat, and Cross Colours.

In contrast to models casted in the Howard Homecoming fashion shows, Gumbs says, “Our models were definitely more edgy, and [their] styles ranged from the runways in Paris to block party vibes. We made sure that we didn’t have just one look.”

Each year, the fashion show had a theme, and in 1996, the perhaps prophetic final theme was “Live or Die.” Student model and singer Kia Bennett (BA ’98) rocked the runway to the opening song, “Ready or Not” by The Fugees.

“It was the style to wear baggy clothes and crop tops and still be feminine and sexy. I was already walking around like I was Aaliyah and a member of TLC. So I came in ready,” she says.

The Richmond, Virginia native adds, “All fashion came from what we wore in the streets. It was a reflection of how we lived and the music we listened to.”

The East vs. West Coast Beef’s Bitter End

Near the close of the decade, the overhyped rivalry between Suge Knight’s Death Row Records and Bad Boy Entertainment culminated with the senseless murders of each label’s brightest star, 25-year-old Tupac Shakur in 1996 and 24-year-old Christopher “The Notorious B.I.G.” Wallace in 1997.

Lee was in Los Angeles with B.I.G. the night of his murder.

“I was at the party with him, at the [Petersen] Automotive Museum in L.A. We were leaving out together, and for some strange reason, I just didn't feel right. And [B.I.G.] looks at me and says, ‘Yo, Tray, what’s wrong man? We're about to go to a party at the Playboy Mansion.’ So I started to perk up a little bit. Then [B.I.G.] goes to the right [to his car]. I go to the left to my car [with] Mark Pitts and a couple partners. Probably two or three minutes later, Mark’s phone rings and he says, ‘Big got shot.’ [We] made a U-turn to the hospital. Mark goes inside and I’m outside with Foxy Brown and a bunch of people. Mark comes out of the hospital, grabs me and says, ‘He’s dead.’ It was an eerie moment in L.A.,” Lee vividly recalls.

The loss of these two rap icons was mourned on campus.

“They provided the soundtracks to [my] college experience,” says Bennett. “I was in my car on the way to a Howard vs. Hampton game when I heard the news of Tupac's passing on the radio. Traffic literally stopped. I also remember waking up one Sunday morning to everyone blasting Biggie at 7 a.m., and that's when I found out he died.

In 1994, Blackman founded the Freestyle Union, which functioned as a hip-hop boot camp for emerging emcees. On the day Biggie died, she hosted a cipher and recalls it was a somber event full of tears and rage. She says Biggie and Tupac’s authenticity is sorely missed.

“There are people whose flow is just as nice as theirs. But it was their level of commitment and sincerity, and their pure love of just rhyming that made them beautiful. You cannot question the genuine love they had for the art form,” she says.

It Wasn’t All a Dream: Hip Hop is Worldwide

In 2001 Blackman became the first U.S. Hip-Hop Ambassador, and she’s traveled to 50 countries representing the culture through performances, workshops, speaking engagements and collaborating with artists local to the country or region.

The self-proclaimed “hip-hop head,” credits the “powerful proximity to success at Howard” during the ’90s with fueling her drive.

“It wasn't just Diddy. It was also the other level of folks [like] the tour promoters, the booking agents, the producers, the engineers, and the people selling t-shirts. There was so much hip-hop entrepreneurship that it just made sense for me to do what I wanted to do,” says Blackman.

Lewis agrees this time period was pivotal, not just at Howard, but as a collective culture.

“People were individually expressing themselves in a way that impacted more and more people until it was everybody. That's really the magic and the beauty – especially when you look at groups like N.W.A. and Public Enemy. [They] were using [their] voice musically to make political, cultural and societal statements that were necessary. That's how hip-hop becomes the voice of the people. It starts with the voice of the one.”

Article ID: 1691