In the new millennium, an edgier, e-version of Russian Roulette emerged: Napster.

Launched six months before 2000 by Sean Parker and Shawn Fanning, the digital music download site revamped music access so anyone in the world could access any song, any genre, anywhere. All you had to do? Hook into that dial-up, search songs, and click the download button.

But veteran DJs prepping their latest gigs could click on the “same” download .mp3 link as students in Founder’s Library did. Results could differ. Maybe your computer never turned on again.

Maybe Outkast’s André 3000 would yell “ONE, TWO THREE-UGNH!” over bulky computer speakers to start ‘Hey Ya!’ in its correct key of C major, cruising at 80 beats per minute.

‘Hey Ya!’ is the first song to reach one million downloads on iTunes, another music platform launched on January 9, 2001. It won the 46th Grammy Award for Best Urban/Alternative Performance.

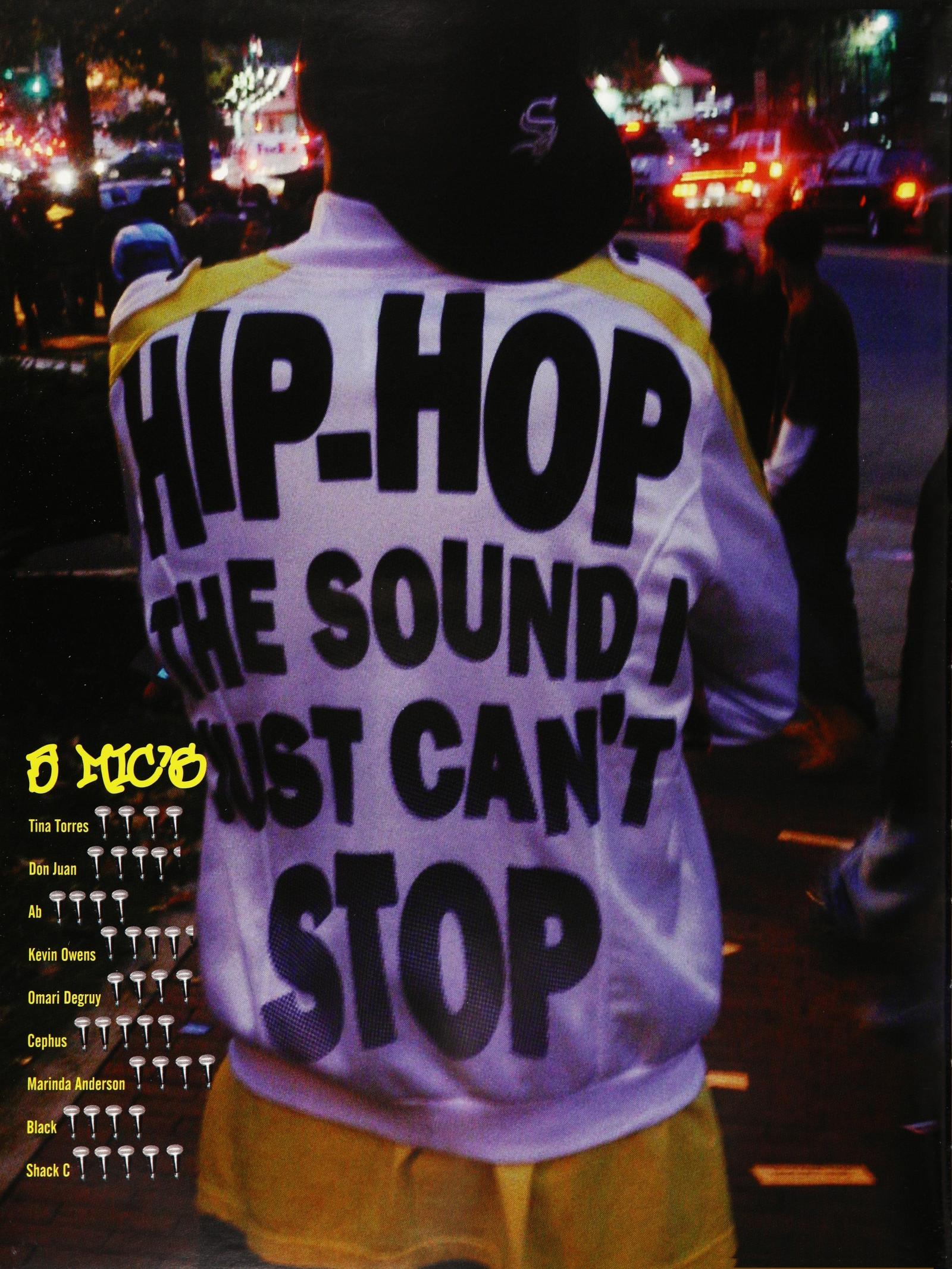

Technology changed the world, but it also digitized hip-hop’s ongoing dominance. The 2000s were a decade that brought along tech advancements that reshaped the music business while Black media outlets strategized new ways to strengthen hip-hop’s stardom.

It even holds one of hip-hop's defining examples of the genre’s ability to convey the relationship between Black people and American politics, a message so unifying that it elects the nation’s first Black president.

Hip-Hop Goes to College

But, even in its worldly success, the genre still faced criticism for the violence associated with it.

Tia C.M. Tyree (PhD ’07) studies the relationship between hip-hop and media and elaborates on BET’s new responsibility of diversifying hip-hop’s perception.

“Coming out of the nineties, BET had an incredibly bad PR nightmare,” Tyree explains. “People were very upset that the network that should have been celebrating us was only showing that which was negative imagery. That's when they became more narrowed in on subjects like HBCUs because, again, you really don't have too many people who are going to say that HBCUs are not important to us.”

Immediate lines between hip-hop and HBCU culture were drawn.

“College Hill,” the fly-on-the-wall reality show that gave insight to the lives, cultures, and connections between HBCU students, was popular on the network. BET began its “HBCU College Tour” in 2001.

College students spent spring break with hip-hop's hottest stars during BET’s annual Spring Bling party in Riviera Beach, Florida with live performances and bikini beach parties. BET then outsourced Spring Bling’s content through a series of live performance music videos, photo catalogues and more with fellow media entities under Viacom such as MTV.

BET’s “106 & Park,” a program dedicated to playing the top-10 hip-hop and R&B hits with hosts AJ Calloway (BA ’97) and Marie Antoinette “Free” Wright, would have special episodes including voter encouragement and gun violence discussions.

“BET had to [ask], what is important to the Black community? What are the positive things that we can showcase? What can we do to make sure that, if this network is supposed to be for Black entertainment, what is it that we know can be a positive influence?” Tyree explains.

Technology Upgrades Howard Traditions

As TV still reigned king, digital download services like LimeWire became melting pots to diversify consumer music access and palettes. Digital file sharing websites also ushered in the rise and the commercial dominance of Southern hip-hop, including its subgenres that dazzled in its infancy such as crunk, early trap, and snap music.

New Jersey native and Apple Music podcast host Nile Ivey (BA ’06) says that Howard’s diverse student body benefited as its traditional, song-swapping process evolved when digital platforms widened access.

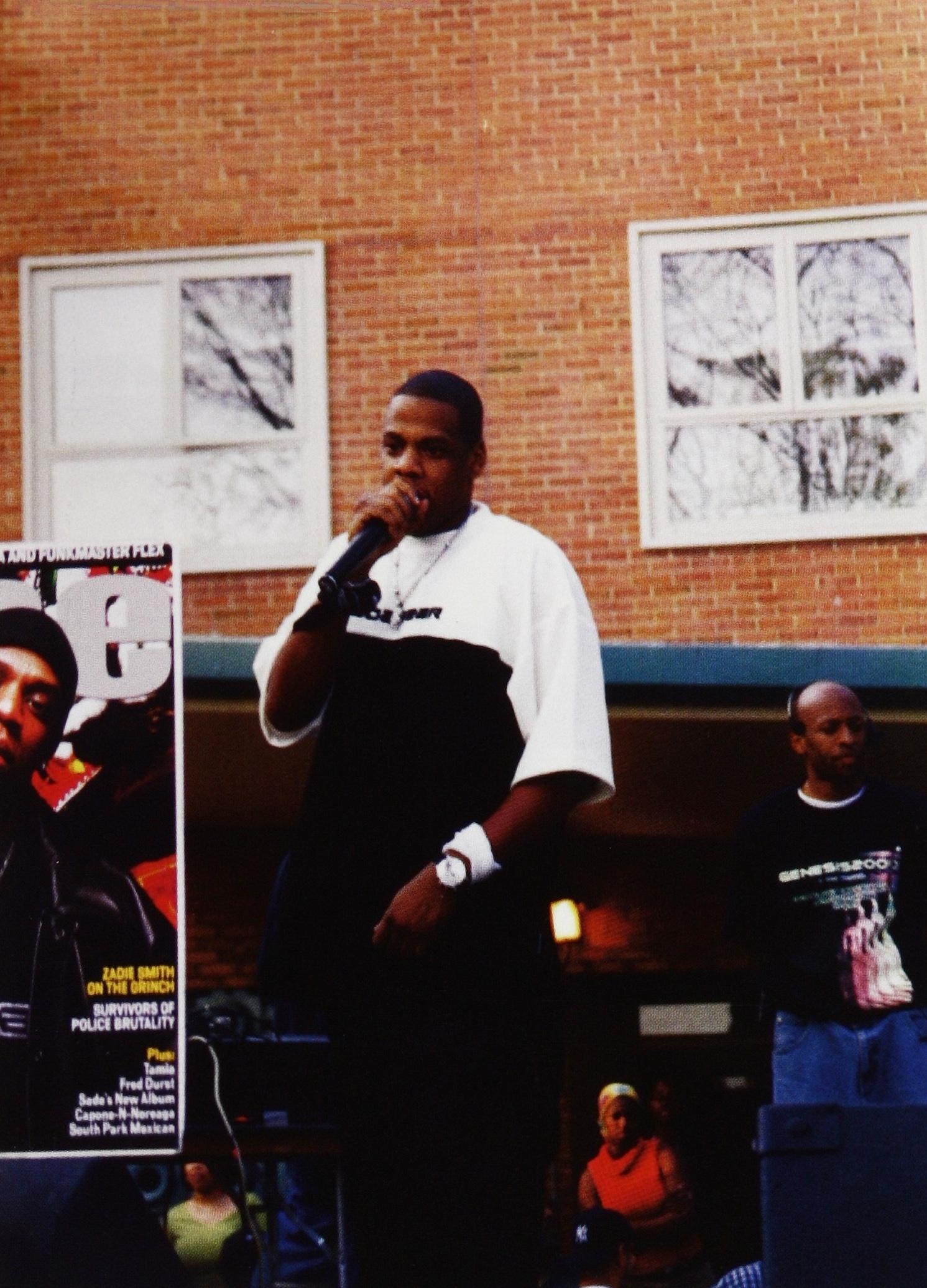

“I’m from the Northeast, and our taste in hip-hop is very spoiled, very pretentious,” Ivey says. “You know we’re going toward The LOX, Jay-Z, DMX, Wu-Tang, but when I got down [to Howard] in 2002, they’re talking about Pimp C, Bun B. Now I’m getting to taste my own medicine. I didn’t know [Southern rap’s] extent and my Southern palette got very exclusive.”

We were the early pirates, so my generation is Napster and LimeWire.”

Tech advancements eventually trickled down to WHBC, the student radio station. Howard’s hip-hop community added another stellar addition to its roster in the 2000s: Angela Hailstorks (BA ’06), better known as Angie Ange, a native of Prince George’s County, Maryland who came to the Yard to follow in the footsteps of Cathy Hughes.

“This Black woman built this billion-dollar radio company, so it was an honor,” Hailstorks says, pointing to Hughes’ creation of the iconic radio late night series, WHUR’s The Quiet Storm.

“When I first came here, my focus was to get on BET... but WHBC was so important for my career. Howard in general created a platform for someone like me to experiment without any experience.”

Hailstorks cites WHUR’s general manager Jim Watkins’ investment in board systems which she refers to as an actual “one stop shop.”

“When our technology got upgraded, it was a game changer. Now we could upload music, commercials and promos all in one place. We were operating how a real terrestrial radio station would, but as college students,” Hailstorks says.

Her deejay aspirations start at some of Howard’s music landmarks. She remembers shopping for fashion at Up Against the Wall where deejays would spin records through loudspeakers to gather crowds. Store manager Al Nice overheard Hailstorks’ bright and projective voice that would be, and is, great for radio.

“He comes up to me and [says] ‘You’ve got a different voice,’ and I said ‘Well, I am a host,’ He said, ‘Ok, well we’ve got Freestyle Friday, you should audition to be a host,’” Hailstorks recalls.

As part of her audition, Hailstorks stood on the corner of Georgia Avenue and promoted the store’s assets to potential shoppers while deejays scratched in the booth during rush hour.

“All the deejays you could think of today that are really popular today, they probably were scratching at Up Against the Wall,” she says.

She credits technology for pushing both the genre and her career forward, allowing a new hip-hop generation to sprout.

“We were the early pirates, so my generation is Napster and LimeWire,” Hailstorks recalls. “We could go to the I-Lab, and everything was Mac, but iMacs were terrible and not user-friendly at the time. My dad brought me a new Mac which came with an iPod.

“Now that my music is on this iPod, I didn't have to keep putting on CDs. Well, when technology like Napster and LimeWire comes out, who’s adopting that? College kids, because we can’t afford to buy CDs [that] were $19 to $20, but you could download for free all day now.”

’04: VOTE or DIE: Hip-Hop Takes the Polls

Vote or Die’s target audience were 18-34 Black voters since they were first-time voters who witnessed the Electoral College override the popular vote between Democratic candidate Al Gore and Republican pick George W. Bush in the 2000 presidential election. The Electoral College gave Bush a tight 271-266 electoral victory despite Gore winning the popular vote by 544,000 ballots.

With the University just 2.5 miles north of Capitol Hill, democracy, political action, and advocacy are three ingredients baked into the institution’s fabric.

Vote or Die having representatives across the hip-hop, R&B and entertainment spectrum really helped its reach.”

“Howard students have always been active in supporting the community,” says historian and Washington, D.C.’s state archivist and public records administrator Lopez Matthews (MA ’06, PhD ’09).

“They protested against the apartheid in South African throughout the ’80s, they called out politicians through The Hilltop. There’s a great photo in the Library of Congress of Howard students protesting the crime conference in 1934 because they were protesting for an anti-lynching bill.”

Vote or Die accompanied other hip-hop-centered political events around the Yard’s election awareness. Amanda Nembhard (BA ’07) was one of The Hilltop’s contributing writers, and covered events such as “The power to choose, which side are you on?” for a discussion on the importance of voting.

Nembhard spoke of the conversations in her article, “How to Court Black Voters Prone to Vote Democratic, Bush and the Black Vote.”

“Many Blacks, who feel frustrated with the state of our nation and believe that neither candidate truly has their best interest at heart, feel it is unnecessary to vote,” Nembhard wrote in The Hilltop on September 14, 2004.

During the 2004 election season, Howard held the very first Hip Hop Caucus on campus with help from HBCU students such as Florida A&M University and local institutions like Georgetown and George Washington University. BET’s public affairs director Sonya Lockett, official hip-hop reverend and current president of the Hip Hop Caucus Lennox Yearwood, and rapper Common were some of the event’s special guests.

“There were celebrities showing us that we have a voice through our vote,” Nembhard recalls. “You’re already attracting a large crowd with music or through music, so it just seemed like an organic way to try and reach the masses.”

John F. Kennedy (BA ’07) (not the former president) wrote for both The Hilltop and Cover2Cover Magazine about student uncertainty regarding the election, and how visits from hip-hop figures soothed young students and encouraged political participation.

“Vote or Die having representatives across the hip-hop, R&B and entertainment spectrum really helped its reach,” Kennedy says. “It was pretty popular. I remember people wearing the shirts, seeing the shirts on different celebrities. I remember like either Election Day or right before Election Day, ‘106 & Park’ talking about Vote or Die.”

’08: Yes We Can – Howard Weaves a Black American Dream

On February 10, 2007, Illinois senator Barack Obama announced his run for presidency to become the first Black president in U.S. history. Vote or Die is a preview to another three-word political phenom that changed America forever: Yes We Can.

“Vote or Die was saying ‘You can affect change,’” Matthews says. “It was reaching out to young people of the 2000s hip-hop generation that a lot of people were trying to discount because it said ‘Oh, hip-hop is just violence and misogyny.’ But no, this is more than that. We can get active. We can be politically motivated.”

People were posting, ‘My president is Black’ as their Facebook status and ‘my lambo’s blue.’... For most of us, it was the first time a lot of us were nationally involved politically.”

Melech Thomas (BA ’11), Mr. Howard of the 2008-09 academic year, remembered being deeply entrenched into Howard’s student organizing world, witnessing the campus’ energy during the Obama-McCain election cycle.

“It was just this very energetic moment,” Thomas says. “That was back when people used to freestyle on the Yard. Howard is everything that they say it was.”

The symbiotic relationship between hip-hop and politics expanded into Howard’s political involvement within their traditional events such as Yardfest. In 2005, Young Jeezy was a standout Southern with his project “The Recession” and performed at Yardfest that Fall.

Jeezy made headlines again in 2007 when he released the Obama anthem “My President’s Black” featuring Nas two months before the 2008 Election Day. It became a hip-hop anthem that lyricized the Black community’s efforts to vote and lift Obama in the polls.

However, Howard’s exclusivity before “My President’s Black” was officially released to the University’s song scourers and deejays. LimeWire and the download platform Morpheus granted Thomas unreleased access.

“People were posting, ‘My president is Black’ as their Facebook status and ‘my lambo’s blue.’... For most of us, it was the first time a lot of us were nationally involved politically,” Thomas says. “It was just such a special song. You can hear it blasting in cars, they've played it at every Howard party.”

The biggest party on campus in 2008 was the election watch party in Blackburn.

“There were at least 3,000 people there,” Thomas says of the ballroom. “Every major news station was there, CNN, NBC, everybody.”

As the night went on, Thomas says that the energy of Howard grew more intense by the minute, until CNN broke the news that Obama had won the 2008 presidential election, becoming the first Black president of the United States of America.

“We went bananas, the entire building shook,” Thomas recalls. “I'm getting goosebumps thinking about it because it was just such a magical moment. Not a dry eye in the house.”

The late-night student crowd spilled out onto Georgia Avenue, where the Howard University community cried, laughed, and cheered at yet another collective contribution to Black history. The Mecca embodied Black America and, of course, hip-hop was there to seal the moment.

“The cops let me use the bullhorn from the top of their car to get everybody hype but keep everybody organized,” Thomas says. “We felt God that night, and Young Jeezy’s ‘My President is Black’ was essentially a gospel song. That’s the best way to describe it: it was spiritual.”

Article ID: 1696