As a child in rural India, Tamanna Joshi (PhD ’22) remembers access to electricity and clean water was lacking for many. Although some perceived these living conditions as adverse, she saw them as opportunity.

While typical children gravitated toward baby dolls and Legos, Joshi would go around her grandmother’s house, find electrical circuits that were broken and fix them with the knowledge she learned in school and at science fairs. She was especially interested in what she called dynamo generators. In simple terms, a dynamo is a generator that produces electricity through an electric field with rotating magnets. She would concoct a current with a little brainpower and tenacity and voilà! A working circuit. In hindsight, Joshi realizes that she was developing a mantra as a child, one that she still keeps in mind to this day: Physics is all around us.

Joshi went on to learn as much as she could about physics in high school and for her bachelor’s degree. In fact, she was in great company. She had classes with around 150 other women and was taught by several women professors and mentors. That’s why she was so taken aback when her journey started to become more niche.

While studying for her master’s degree, the concepts and fundamentals of physics looked the same, but the people around her started to look a little different. She went from being surrounded by plenty of brilliant women interested in science to being one of just a few. Some of the women Joshi went to school with dropped out due to family issues. But Joshi thinks that gender norms and a lack of support played a role as well.

“Having somebody telling you all the time … you’re not smart enough, you can’t do it,” she says. “Sometimes, some people just believe in that, and it’s not true.” Joshi went on to pursue her doctorate at Howard, focusing on condensed matter and materials physics.

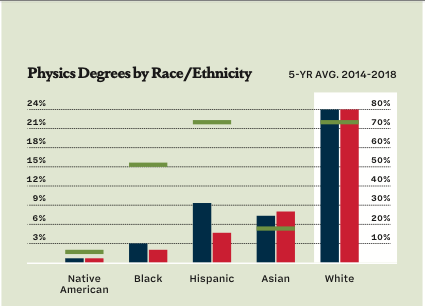

Joshi’s story is familiar to many women who choose to pursue their PhD in physics. According to the American Institute of Physics, based on the data from 185 doctorate physics departments across the nation, a little over 20% of degrees are conferred to women. Between 1973 and 2012, 803 women of color earned their doctorates in physics compared to 22,172 white men, according to figures from Quartz and the United States National Science Foundation. Contrast that at Howard University, close to 55% of degrees are conferred to women, notably, women of color. That is more than double the national average of women PhD physics candidates. This past year, Howard graduated three women, including Joshi. Two of them Black; all three come from minority backgrounds.

Having somebody telling you all the time … you’re not smart enough, you can’t do it. Sometimes, some people just believe in that, and it’s not true.”

Finding Support

Growing up in Nigeria, Farinre Olasunbo (PhD ’22), can similarly attest to seeing women in the field of science not being supported by their community because of societal expectations put on them. Olasunbo grew up seeing women constantly being told they were not smart enough to pursue science. Luckily, her family was different: her father encouraged her to be the best that she could be. She remembers being the best overall graduating chemistry student in high school because her family provided the resources she needed to grow. Today, she is a planar process engineer at Intel, having studied computation physics and condensed matter physics during her doctorate work at Howard.

It’s clear that community support helps foster better students. In Olasunbo’s case, she makes the connection that the field of physics, uniquely, “has the lowest representation of women compared to other sciences, which is largely a result of racial and gender discrimination.”

She continues, “Women in Africa are trained to be good wives to their husbands, homemakers, mothers from childhood and not be too career inclined because society believes these are your primary responsibilities. Therefore, this discourages them from pursuing careers in male-dominated fields like physics.”

Kenisha Ford (PhD ’22) points to her story as an example of how the physics industry is not as inviting for women, especially women of color. Ford began her journey in science and engineering as a child because she wanted to be like her mother, who was an engineer. During her senior year of high school, Ford had her very first “aha!” moment when she built a Goldberg apparatus in physics class. A Goldberg apparatus is a set of tasks that work in succession and trigger one event after another until the desired outcome. A lightbulb went off in Ford’s head because she realized that, whether it’s a bridge, mousetrap, car, or a Goldberg apparatus, physics can be applied to everything.

So all these years, lots of progress, but very, very slow progress.”

Momentarily, Ford’s career in physics blossomed. She went on to pursue her bachelor’s in physics at Spelman College, where she finally had the opportunity to not be the only Black woman or student in the class. There, she worked as a research associate at two universities in condensed matter physics and modeling computational fluid dynamics and also for the federal government. When the craving to go back to school was knocking at her door, she answered, but only had one requirement: It must be a doctorate in physics where she would be able to apply the principles of physics to breast cancer research.

Joining the Club

As a doctoral graduate of the 2022 Howard University physics program, Ford explains how connecting with other Black graduate students in other disciplines at Howard allowed her to feel more comfortable in the space. Even though Ford is doing what she loves, physics is no easy beast to tame. On top of the difficulty of the subject, being both Black and an American woman can create a very isolating experience for many. The statistics of Black women who graduated with their PhD in physics can support this social risk factor.

“As I neared graduation, a classmate of mine [was] the sixth Black American woman to graduate from Howard’s physics department. That made me, coming out this year, the seventh. Since the first Black woman [received a PhD in physics in the United States] in the 1970s, there [has] barely [been] over a hundred [women who have received a PhD since]. I think this year I was like the 111th African American woman to get a PhD in physics,” Ford says. “So all these years, lots of progress, but very, very slow progress.”

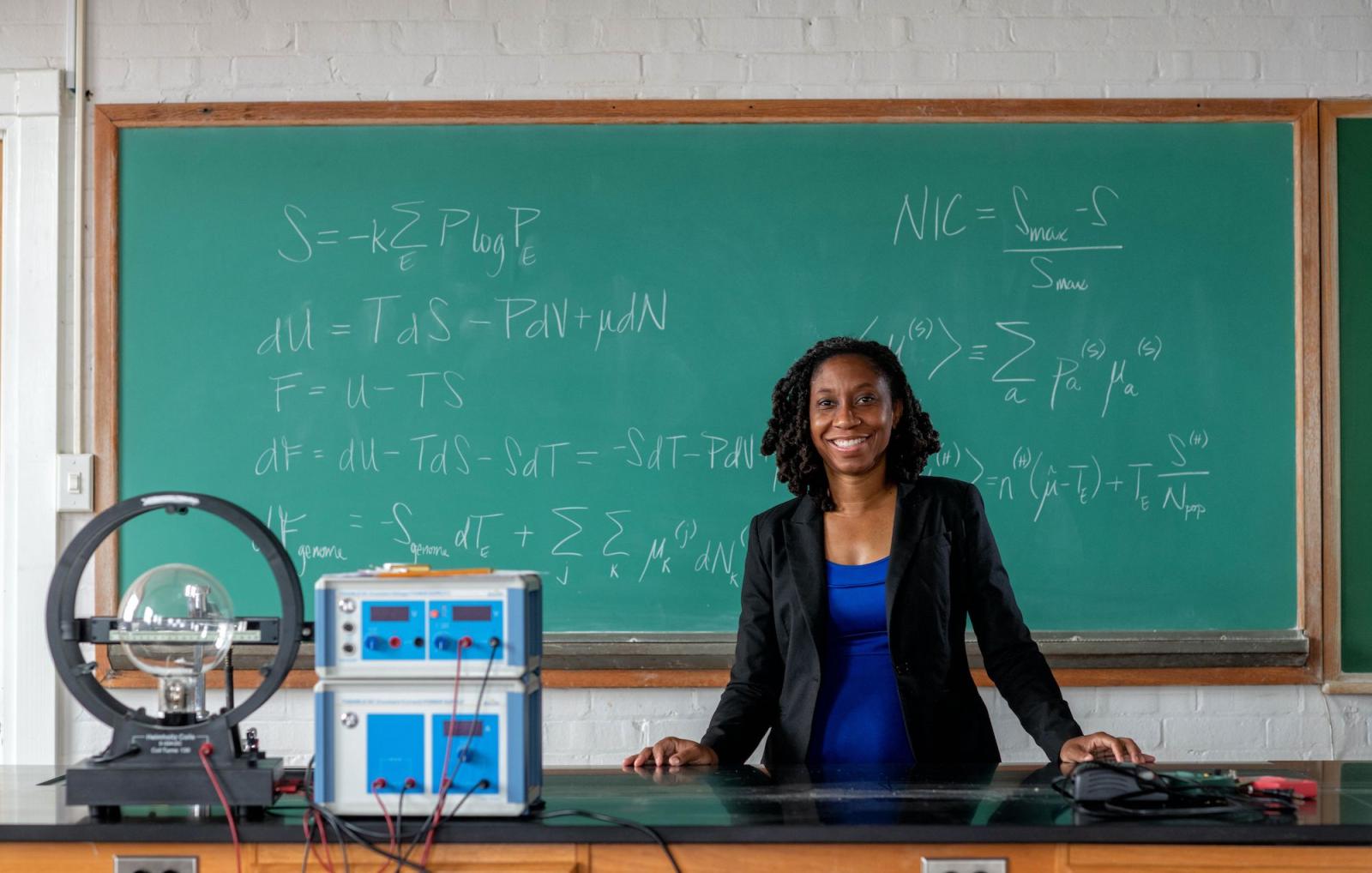

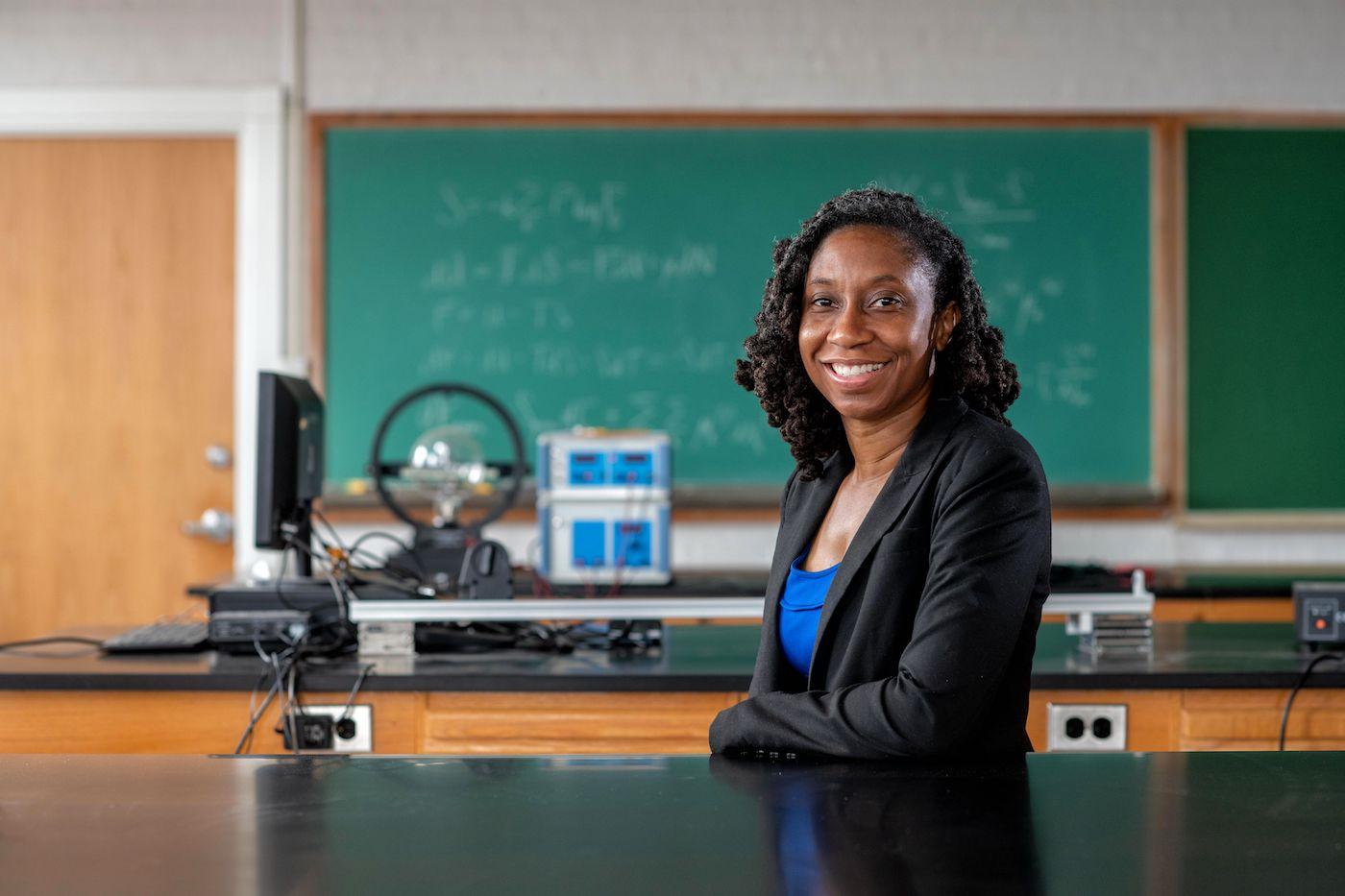

Quinton L. Williams, PhD, professor and chair of the Howard University Department of Physics and Astronomy, highlights how the benefit of being surrounded by people who look like themselves helps foster community support. “Students are in an environment where you can be yourself. You can focus on the physics and not whether you belong. We want to show that you are a person. We care for you. We want to make this work.”

Ford’s emphasis on the fact that there is still progress, no matter how slow, should be noted. A research report from the American Institute of Physics shows that since 1980, women who have earned a PhD in physics have gone up close to 15%. The industry is changing, but it still has a long way to go.

Ford provides a solution to this obstacle that we see with the lack of women in the physics profession. She explains, “HBCUs are an easy place to increase recruitment. If you want to increase the number of Black women in programs (and Black students in general), start with the spaces where more Black people are graduating from.” Ford also pays it forward to upcoming Black physicists through her nonprofit started with her mother and sister. Science and Math Innovators Inc. focuses on children in grades K-9 from underrepresented groups to dispel the “myth” of how a scientist looks. Joshi and Olasunbo say they also chose Howard because of the mentorship the professors provided and the community it fostered.

Olasunbo doubles down on the idea of providing more resources to recruit women of color in physics. She clarifies, “I believe if more scholarship opportunities are available for women, most especially women of color, they would be encouraged to pursue a degree in physics. We also need more support groups on campuses to help encourage these women and provide all the support and resources they need to thrive and succeed.”

The solution Joshi provides focuses on mentorship. Joshi is a strong believer that younger women and girls need to see someone who looks like them in the physics space. The discrimination that women in physics face is not going to stop, and she sees this gap as an opportunity to encourage up-and-coming physicists to persevere just like Howard encouraged her to navigate her cultural differences.

“I have a responsibility to contribute to the community, to young women or to anybody who would benefit from my skills,” Joshi says. “At Howard, everyone has different backgrounds and stories – you get to discuss their stories and struggles.”

Article ID: 1096

Keep Reading

-

The Power of High Temperature and UV Rays

Doctoral candidate in physics Kenisha Ford uncovers a potential

pathway for new targeted breast cancer treatment.