At the gallery Lisa Dent (BFA ’92) helms in the city regarded as Connecticut’s arts capital, a major exhibit in 2020 examined the New Haven Nine, members of the Black Panther Party accused of the 1969 murder of a purported FBI informant.

The socially distanced, masked audience for “Revolution on Trial” at Artspace New Haven included art-lovers of various races, says Dent, the gallery’s first-ever Black leader. But the audience didn’t mirror New Haven, where people of color comprise 56 percent of the population. If a representative sample of residents didn’t turn out for a show whose themes resonate in today’s racially charged times, that owes to Artspace’s history of not welcoming them in.

“It was clear that people needed to be invited in ways that didn’t exist before. Going forward, how do we create a space where they feel they belong?” asks Dent, executive director of Artspace.

When she started that job in Spring 2020, she became the first in an all-Black triumvirate of theater and arts executives, all hailing from Howard, who were hired to move New Haven’s arts and culture sector into a more diverse future.

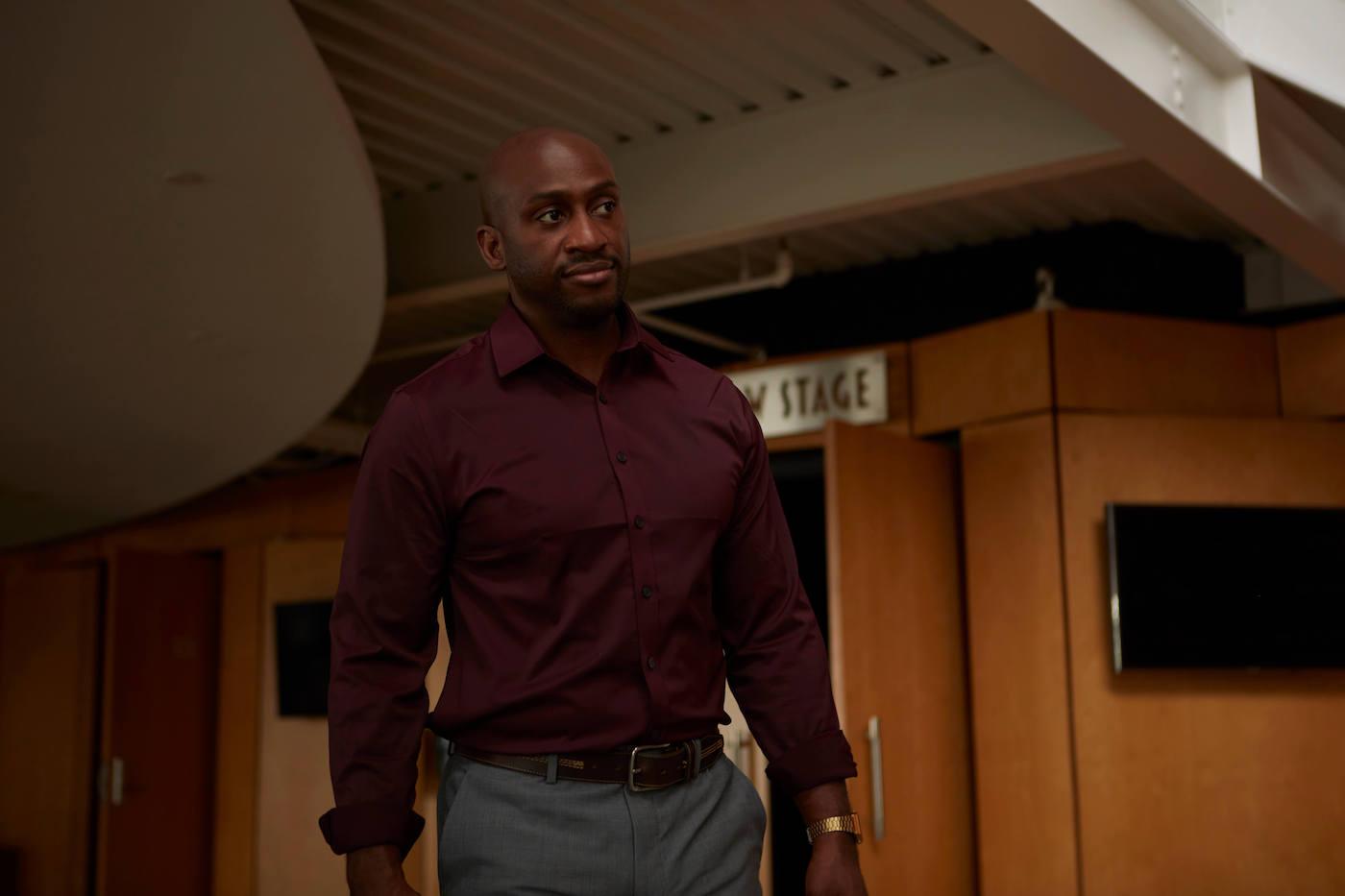

In Fall 2020, King Kenney (MBA ’17) became the first Black marketing and communications director at New Haven’s vaunted Long Wharf Theatre, winner of Obie, Pulitzer and Tony awards and incubator of plays that ascend to New York City’s Broadway. And in April 2021, Anthony McDonald (BFA ’10) became the first Black vice president and executive director of the Shubert Theatre, another of New Haven’s esteemed art houses.

Diversifying the Artists – and Their Audiences

New Haven itself is at a cultural crossroads. “Older, white audiences are dying here. If we don’t open the door and get more diverse patrons to support us in the community, we won’t be here much longer,” says McDonald, who’d been a playhouse manager in New York City before the pandemic shuttered Broadway and eliminated his job.

In New Haven – where the city’s first Black arts and culture director uses terms like “anti-racism” during public discussions – those three Howard alumni say they are seizing opportunities rarely afforded African-Americans in a mainstream arts world where whites still dominate. They are, they say, being given the rare chance to shift and enlarge the conversation about what constitutes art; to cultivate art patrons of color; and to feature more artists of color presenting their particular world views. That kind of change requires an approach that white leaders of these art spaces hadn’t considered before and likely could not achieve on their own, the three say.

“You are seeing people trying to change the optics,” Kenney says, referring to his mainly white colleagues at Long Wharf. “But they think that just by putting up a show people will come. What they don’t understand is you have to go into the community to make that kind of real-world change.”

Historically, theaters tend to market toward affluent, white communities, Kenney says. Programming that highlights non-white talent sends the theaters “scrambling to find an audience that is unaware of their existence.”

He continues: “From a marketing standpoint, the default is to go to Black churches when producing ‘Crowns.’ Or if they produce ‘The Joy Luck Club,’ they will go to the nearest Chinatown or seek out partnerships that introduce them to members of the AAPI community. That said, it’s not enough to introduce yourself to a community in that way and then disappear. You have to market all your programming to BIPOC communities, mindful of the fact that they are not monolithic.”

Kenney, McDonald and Dent have made forging relationships with a wide swath of city residents their top priorities. They’ve made seemingly small overtures that, over the long haul, can have a big impact. For the first time, for example, the Shubert Theatre co-sponsored the last New Haven Caribbean Festival, prominently displaying the theatre’s logo during that event. The Shubert hosted a pop-up COVID-19 vaccination clinic. “That was a way we could give back to the community and say ‘Thank you. I want to see you in the theatre, so let me help you get vaccinated,’” McDonald says.

Marketing director Kenney has been pushing the limits of what his predecessors deemed suitable to stage at the Long Wharf. A Black comedy show, for example, would draw a packed house of Black people, he says. Matter-of-factly, he reminds his Long Wharf colleagues that their past staging of “Satchmo at the Waldorf,” about the pioneering trumpeter Louis Armstrong, drew such a diverse group of theatergoers that its run was extended.

“When you put someone like myself at the table, it changes the conversation,” Kenney says. “I hope the people who hired me are saying ‘We know what we’ve gotten ourselves into.’”

Beyond the College Crowd

Artspace’s Dent says that the three of them are trying to learn precisely what potential art patrons in New Haven desire from the city’s arts venues. She describes New Haven as a town-and-gown city, where the well-heeled host arts fundraisers with few minorities present, even though New Haven also has its share of well-to-do Black, Latinx and other residents of color.

She also describes New Haven as a straight-up college town, facing particular challenges in sustaining the arts.

“Not only is there Yale, but four other undergrad institutions [are] in the city,” she says. “While it is diverse, it’s also a very transient population. One of the challenges many art spaces have had over the last 20 years is ‘How do we stay in the minds of people as they are moving to other parts of the country? And how do we center the stories of artists who live here full time? How are we going to be an inspiration to people outside the city who visit?’”

Since she landed in Connecticut, Dent has been circulating through BIPOC neighborhoods in the city and talking up Artspace as a center dedicated to emerging artists and boundary-breaking art. “I’d say, ‘Artspace,’ and they’d scratch their head,” Dent says. “So many of them had never heard of it,” says Dent, who previously worked as a curator and gallerist before focusing on artist development. If they had, “they didn’t feel like Artspace was for them. I know how to change that. … [It] doesn’t mean shuttling school children through the door once a year. It means showing the public the complexity and beauty of the diaspora coupled with a welcoming and inclusive environment.”

Kenney, who’d been marketing director at Duke Performances at Duke University, says New Haven’s racial and class diversity are much of what attracted him to the job. He’d spent the last several years job-interviewing at arts organizations that he doubted were ready to do more than pay lip service to creating diversity, equity and inclusion in the arts world.

“We have such an opportunity to do great things here,” Kenney says. “Across the country, so many of us are dealing with imposter syndrome because we get to these arts organizations that do not position us to succeed and end [up] performing five white plays anyhow. … I don’t have to do that where I am.”

“In this field,” Dent says, “you’re always trying to find the right place to work, not just as a curator, but where the institution is interested in structural change and you are seen as a complete human being

And that, McDonald says, “doesn’t mean doing one or two Black shows a year, when you’re putting up 30 shows. If we have 30 shows, 15 or 20 of them have to be diverse … if the entire community is going to see itself on stage. And this cannot be happenstance.”

The trio says they feel emboldened and supported in their work. The city of New Haven’s director of arts and culture sits on the Shubert’s board of directors. She was the first person to dial up and congratulate Kenney about his new job. “We are creating our own cohort, so that, in these places of power, we can have each other’s back,” McDonald says.

Dent agrees. “We are having very different conversations right [now]. I am having to help my board understand that all of the people with incomes that would allow them to participate in a fundraiser or board membership are not white. … We could fill our board with more people of color who have the income and the influence to support our programs. This is where the opportunity lies for New Haven. What we are doing here could be a model for the rest of the country.”

Says King: “We’re about to partner and collaborate in some very different ways.”

Coming Attractions

Howard alumni who’ve been tapped, since early 2020, to helm or hold key positions at the Long Wharf Theatre, Shubert Theatre and Artspace New Haven said arts patrons should expect to see New Haven, Connecticut’s arts get, if you will, even more mixed up – more fully reflective of the people who occupy this land. They will be dishing some breakout stuff.

The Shubert’s Fall and Winter 2021 lineup, for example, includes reproductions of Broadway’s “Anastasia” and “Hairspray,” but also “The Hip Hop Nutcracker,” replete with dancers of that genre and a DJ. Artspace’s annual festival, called City Wide Open Studios, was renamed to Open Source to provide space to for more than just privileged individuals. Open Space encourages all members of the artmaking BIPOC community to feature their work, both virtually and in person.

Article ID: 141