In the thumbnail sketch of Wayne A. I. Frederick’s story, his mother is the Trinidadian primary nurse who insisted that her son select Howard University because of his sickle cell disease and because Howard had a well-established sickle cell disease center. But the description does not fully capture the influence of Frances Tyson-Hill, Dr. Fredericks’s first and most powerful role model in medicine.

Tyson-Hill accomplished her nursing career while setting high expectations for her three sons. Wayne, the eldest, was born in 1971 in Port of Spain, Trinidad. His father was a policeman who died just before Wayne turned three. Alongside his mother, the other major shaping influence in his life was sickle cell disease.

His family was acutely aware that in Trinidad and Tobago, children with sickle cell disease were not expected to make it out of childhood. Every birthday was a landmark. Tyson-Hill prepared over-the-top celebrations and brought together the entire neighborhood for celebrations. Wayne’s grandmother, Christine Tyson, explained to him that he had sickle cell anemia. She told him about the severity of the condition and pain crises that he would experience.

Coming to terms with his own daily reality of dealing with a medical condition and the impact of his mother’s own aspirations of becoming a doctor subtly steered him to his own dream of studying medicine.”

The sickle cell limited his participation in sports; even going to the beach could be painful. He was hospitalized a couple of times every year due to the illness. Coming to terms with his own daily reality of dealing with a medical condition and the impact of his mother’s own aspirations of becoming a doctor subtly steered him to his own dream of studying medicine, Dr. Frederick recalls.

In many ways, Tyson-Hill was the perfect role model for a child committed to medicine at such an early age. She worked for five decades serving island communities as a primary nurse. However, nursing was not Tyson-Hill’s original career choice. She had aspired herself of one day becoming a physician. But she was thwarted by discriminatory attitudes in the 1960s about the capabilities of women in leading professions which prevailed in the Caribbean, just as they had in the United States at the time.

Growing up, Dr. Frederick consumed most of his free time at home reading. Much of the rest was spent marveling at his mother’s medical work. As a nurse and a district health officer, Taylor-Hill would spend hours dedicated to ailing people who would sometimes call her at the family home. Young Wayne was unfazed, even by the goriest of medical scenes, amazing his mother who herself had trouble stomaching the grisliness. His true thrill came about when he would see patients transition from ill to healthy, a pleasure he would always cherish as a physician.

The Influence of Sickle Cell Disease

Sickle cell disease played a large part in his education. As a medical student, Frederick’s set his sights on becoming a hematologist oncologist. He also dreamed of finding a cure for sickle cell disease. Sometimes he would practice the Nobel Prize speech that he imagined that he would be called on to give as a reward for the discovery.

Early life challenges with disease often sparks the imagination of future physicians, according to Clive O. Callender, MD, the Howard University surgeon who mentored Dr. Frederick in the College of Medicine.

“I’m a surgeon and I had tuberculosis (TB) when I was 15,” Callender said. “At that time, TB was not curable. So the options for me surviving were not good, so I understand how whatever disability you have can influence your path into medicine. Sometimes obstacles are just steppingstones to success.”

Dr. Frederick walked through Howard’s gate in 1988 enrolled in the accelerated BS/MD program which would allow him to earn an undergraduate and medical degree within six years. Because of Howard University Hospital’s highly reputable Center for Sickle Cell Disease, he knew he could be immersed in academic excellence while receiving good health care for his sickle cell.

Dr. Frederick’s leadership is quiet yet stern, forceful yet determined, and focused on a level that is stealth yet productive. Dr. Frederick’s leadership has been a gift to Howard University and his leaving the institution at this point brings about a magnanimous change at every level. — Gina Spivey-Brown, PhD, MSA, RN, dean, college of nursing and allied sciences

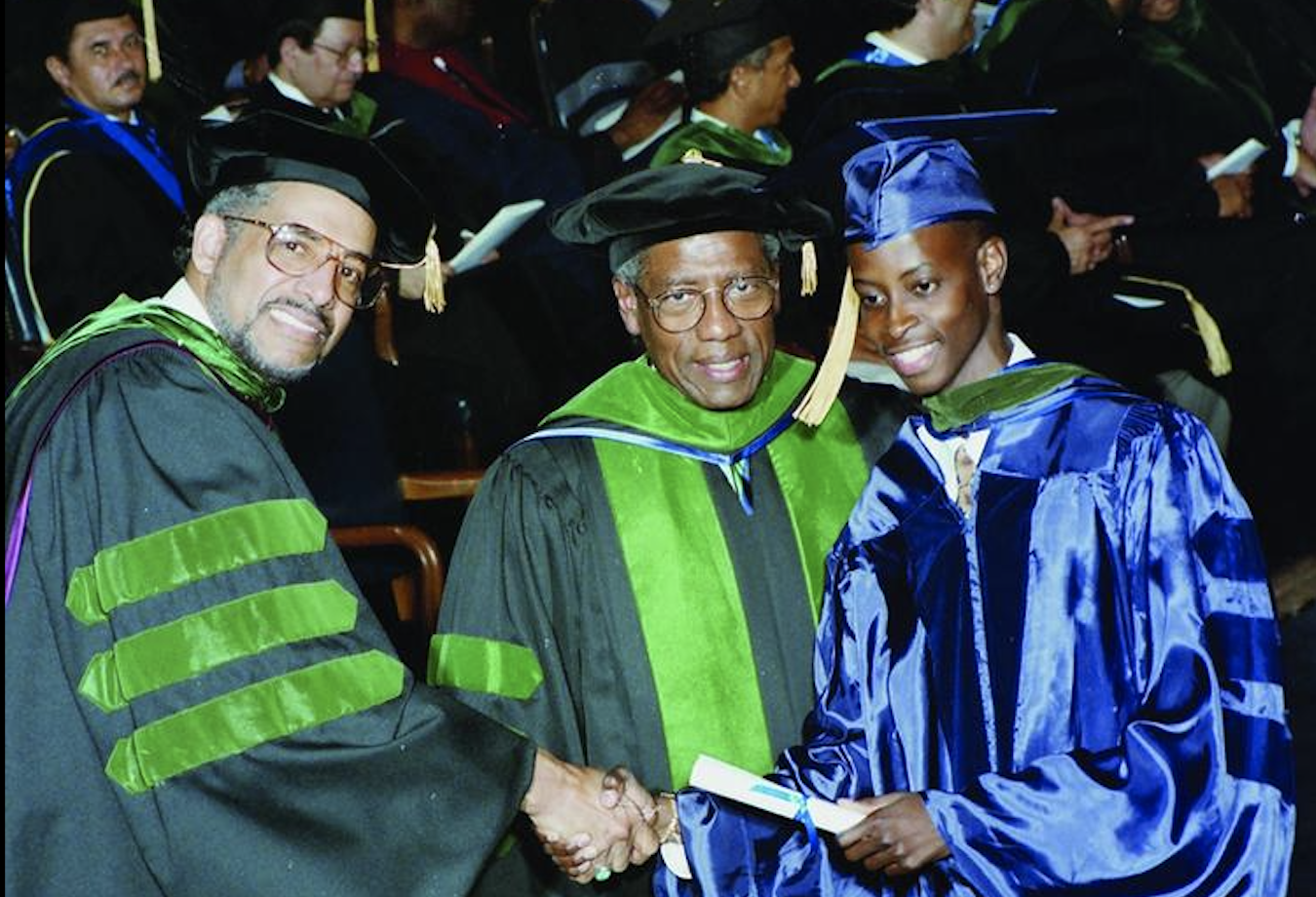

Through the mentorship of Callender and another legendary Howard surgeon, LaSalle Leffall Jr., M.D., FACS, Dr. Frederick fell in love with the discipline of surgery. Over time, his interests narrowed even further to cancer surgery, and then to treating gastrointestinal cancers. Dr. Frederick has always found this choice of specialization ironic: the intestines and open abdomen was the one area of body that repulsed his mother. “She was not crazy about seeing the inside of people’s abdomen.”

Article ID: 1211

Keep Reading

-

A True Son of Howard

Dr. Frederick accepted the offer that Howard University made to him to join the freshman class in 1988. It was the beginning of a journey that would define his life.

-

The 17th Presidency: A Transformational Decade

The Story of Howard University’s 17th Presidential Administration, led by Dr. Wayne A. I. Frederick

-

The Family Tree

Dr. Frederick attributes his success to the close relationships of family and friends he’s held through his life.