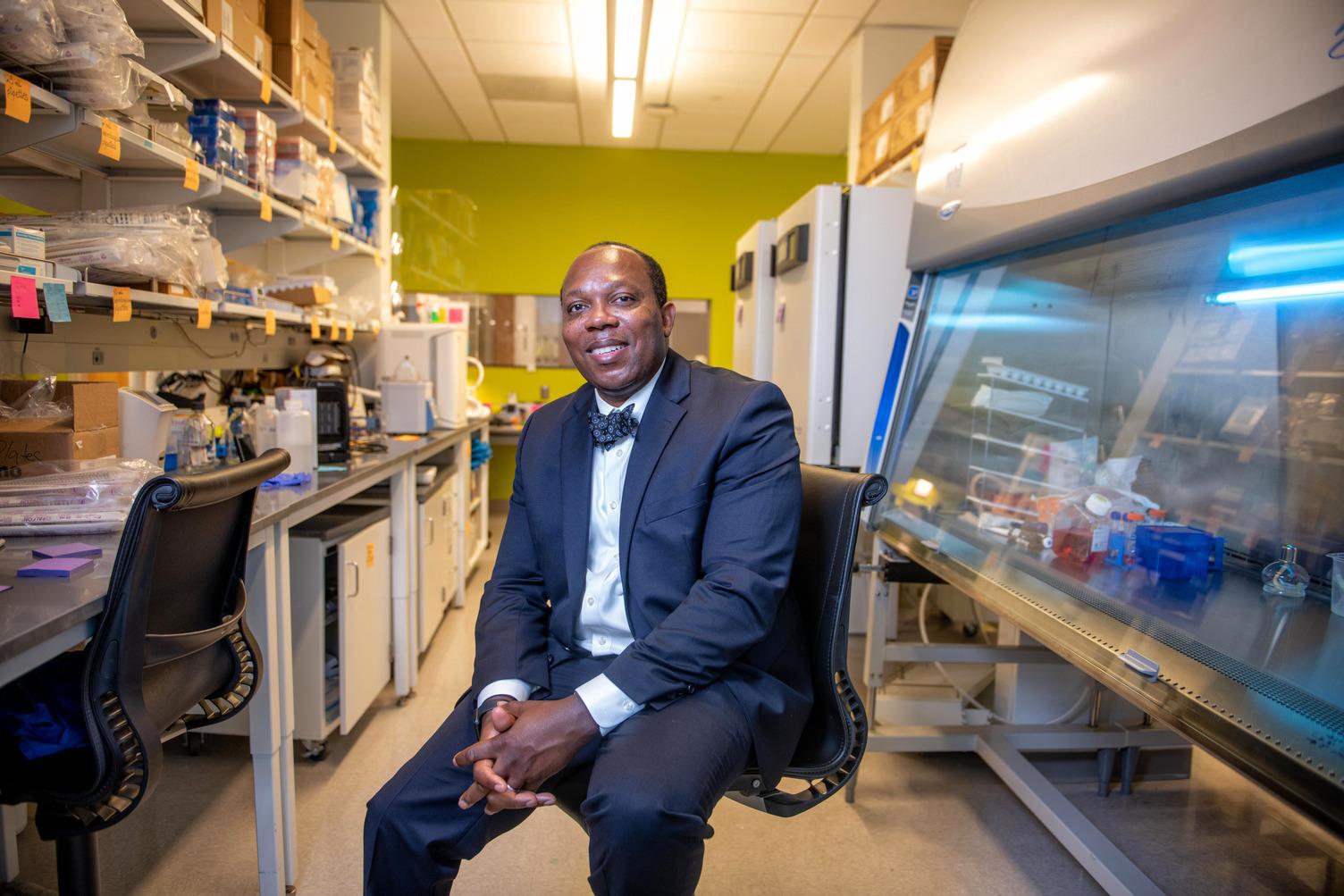

Evaristus Nwulia, MD, MHS, is leading a five-year study at Howard, which began in 2019, that will hopefully one day give doctors the ability to take a sort of “colonoscopy” of the brain – by taking nerve cells from the nose.

“We can’t take your brain tissue like in a colonoscopy because it’s not ethical to cut the brain,” says Nwulia, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences as well as the director of the Translational Neuroscience Laboratory. “But we can take something close to that.”

Studying Alzheimer’s can be particularly difficult because researchers have limited access to the brain, where the disease is centered. It is also challenging to predict or prevent the occurrence of Alzheimer’s or other diseases because medical professionals can’t take brain tissue from a living person the way they can evaluate or take samples of other parts of the body.

People who suffer from Alzheimer’s or dementia often lose the ability to identify smells before they begin to lose their memory."

The part of the brain that controls a person’s sense of smell also plays a critical role in memory and other cognitive functions. According to Nwulia, people who suffer from Alzheimer’s or dementia often lose the ability to identify smells before they begin to lose their memory. Additionally, animal studies have shown that damage to the sense of smell can affect memory formation.

“It makes sense for us to consider using nerves that we recover from the nose to study Alzheimer’s because those nerves play a role in the development of [the] disease,” Nwulia says. “Either they are involved early or they directly [affect] the pathology in the brain.” These nose cells could either help predict the likely occurrence of Azheimer’s, or damage to these cells could, in some way, cause Alzheimer’s to occur.

The study has multiple components. First, the team collects nasal nerves from participants and follows them over time to observe whether they develop Alzheimer’s disease. The second component involves testing and studying the nerves they collect to identify how the cells respond to stress and how they recover from injury.

Early findings from the study appear to confirm some of the team’s initial hypotheses: First, nose swabs can successfully be used to study the part of the nervous system that is most affected by Alzheimer’s. And second, people who are genetically at greater risk for developing Alzheimer’s have nasal nerves that develop and recover more slowly.

“We are suspecting that this inability of people with genetic risk of Alzheimer’s to produce more nerves to replace injured nerves may explain why their brain shrinks more with increasing age,” Nwulia says. “Another implication (or significance) of this is that if COVID-19 makes people at risk to lose their ability to smell food, it would take them very long to recover their ability to smell, because these nerves develop and recover slowly in this group of individuals.”

Nwulia adds that they are actively studying the “complexity” of the disease, particularly why some people who might be genetically predisposed to develop Alzheimer’s might not get the disease, whereas others who are less likely to develop it genetically, end up falling victim to the disease.

Ultimately, the study, which has received funding from the National Institutes of Health, hopes to reveal insights that can be used to predict the likelihood someone may develop Alzheimer’s disease as well as information regarding how to prevent Alzheimer’s or reverse damage that may lead to the disease’s development.

On a deep and personal level, Nwulia understands the potential impact this study can have – both on individuals who suffer from this devastating disease and the family members who care for them.

“When my grandfather developed Alzheimer’s disease … the psychological effect and so forth was so extensive and crushing to my family,” Nwulia says. “[During that experience] I thought, ‘I will commit the rest of my career trying to make sure that people don’t go through that.’”